Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 17

In the previous chapter, we introduced Shôami Denbei who created the concept of mokume-gane, and his gorgeous mokume-gane work. In this chapter, we would like to tell you about “guribori” which is linked to the advent of mokume-nane techniques.

It is said that mokume-gane techniques originated in the early Edo period, in the guribori tsuba created by Shôami Denbei. In guribori, different colored metals such as copper and shakudo are stacked alternately and fused, then arabesques and spirals are carved in so that the metal layering design is visible in the carved parts. There is a theory that this may have been influenced by the folk patterns of the Ainu, but it is generally believed that the roots lie in the Chinese lacquered “Guri.” This chapter will be devoted to “guri.”

Tsuba by Akita Shôami Signed Shôami Denbei residing in Dewa, Akita Middle of the Edo period Shakudo

Photographed fom Tsuba Taikan by Kawaguchi Wataru (Tôken Shunju)

The technique of applying the sap of the Japanese sumac tree to utensils is known as lacquering. Guri is one of the ancient lacquer techniques of China. Nowadays, most people are familiar with the likes of Wajima lacquer or Tsugaru lacquer, with tableware or gold makie works of art. Coating wooden utensils with lacquer makes them resistant and long-lasting. In ancient China, it was common to coat multiple layers of lacquer onto wooden items to achieve considerable thickness, and then carve this into three-dimensional patterns. These swirling patterns that looked like continuous warabi bracken were called guri. The arabesque patterns which had spread around the world since ancient times were further refined with abstract heart or swirl patterns appearing. Through the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, this Chinese lacquer came to Japan at the same time as Zen Buddhism, and was prized for use in tea utensils or incense containers. In Japan, the swirl patterns were called “kurikuri” which is how it came to be known as guri. The sound came to depict the pattern.

Guri wreath patterned tea bowl stand Song Dynasty Lacquer Property of Toyo National Museum ©Tokyo National Museum

Subsequently, this was imitated in Japan to carve designs on wood and apply lacquer to make Buddhist altar objects, becoming the origin of Kamakura-bori. There are masterpieces among Japanese made lacquer inro from the latter part of the Edo period believed to be of similar origin, showing us that such patterns circulated widely at the time.

Inro and netsuke Latter part of the Edo period lacquer Property of Mokumegane Research Institute

And going further back in China, it is said that the technique known as ”Saihi” which was mostly seen during the Southern Song dynasty is at the origin of guri. In this, yellow and orange coatings were applied alternately, with the final surface layer being black, and, as geometrical patterns were carved out, delicate layers of colored lacquer became visible. There are only a very few pieces still in existence. Both the Tokyo National Museum and the University Art Museum of the Tokyo University of the Arts have several pieces in their collections.

So, please take another look at the guribori tsuba made by Shôami Denbei. There is no doubt that the swirly pattern carved into the metal layers resembles the guri technique. And the reason why Denbei’s guribori is called the ancestor of mokume-gane lies in the similarity of the technique in carving down the layered metal. The greatest characteristic of the guribori of the Akita Shôami school, which started with Shôami Denbei, is its full three-dimensional effect. The carving is bold but there is refinement within the scale and massiveness giving it the characteristics of being an ancestor. It is also well-rounded, giving an impression of the same level of outstanding technique seen in the Southern Song dynasty incense containers

Guribori incense container Meiji period lacquer Japan Mokumegane Research Institute

Shôami Denbei further developed this guribori technique and created the mokume-gane technique that produces the gorgeous patterns such as those we described in the previous issue. He was able to produce intricate patterns by carving and twisting the layered metal billets and then pounding them down with a hammer.

Further advances in guribori technique were not immediate and happened in the latter part of the Edo period. Takahashi Masatsugu who was a craftsman specializing in sword tsuba was active during the Bunka and Bunsei eras (1804-1829), and left elegant and refined guribori pieces for posterity. Subsequently Masatsugu’s adopted son, Takahashi Okitsugu, specialized in guribori and mokume-gane. Looking at the magnificent existing sword fittings by the Takahashi school, starting with Masatsugu and Okitsugu, it seems appropriate to say that this was the pinnacle of guribori and mokume-gane techniques.

Guribori tsuba Signed: Takahashi Masatsugu (hanaoshi) Middle of Edo period Silver, copper, shakudo Property of Japan Mokumegane Research Institute

Guribori tsuba Signed: Takahashi Okitsugu (hanaoshi) Middle of Edo period Copper, shakudo Property of Japan Mokumegane Research Institute

At Mokumeganeya, we have adapted the technique of guribori, with its long history, to modern times, and are putting our all into producing wedding rings that our customers can wear forever.

Reference documents: Tokyo National Museum Masterpiece Gallery

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 16

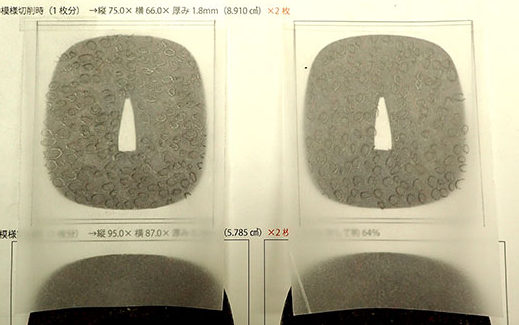

In the last chapter, we told you about Shôami Denbei who made the kozuka which is acknowledged to be the oldest and most beautiful example of Mokume-Gane. The CEO of Mokumeganeya, Takahashi Masaki, made a reproduction study of this Mokume Gane kozuka signed Shôami Denbei, made of gold, silver and other metals, and an Akita Prefecture designated cultural property, in 2003 in order to elucidate this outstanding design that was particular to Shôami Denbei and not seen elsewhere. We will give an overview of this project here. This represented the first such study of the design techniques of Edo period Mokume Gane. Below is an excerpt from the study thesis.

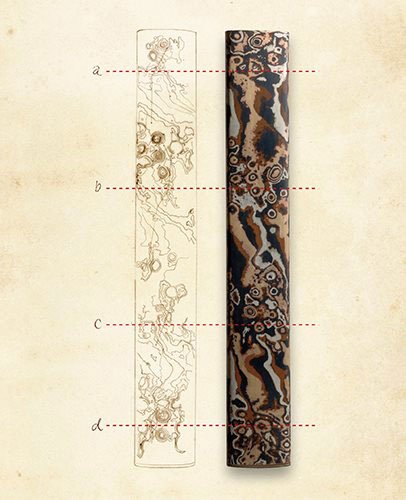

The first step was to enlarge a photograph of the Kozuka knife and trace the pattern in order to find out how many types of metal has been used and how they had been stacked. Within the detail of the pattern, the intricate changes in the materials, reminiscent of the fine contour lines on a map, are laid out within a framework of as little as one millimeter square. The technique of Mokume Gane consists of first carving down a metal stack, or billet, using tools such as a chisel, and then creating the pattern by using a hammer to forge it flat. By using this process, the order of the metal layers remains the same whichever portion is extracted to reveal the pattern on the surface.

It became clear, as a result of the observation, that the order of the layers was reversed at the boundary between the A portion and the B (copper) portion of the pattern. Comparing the trace drawing to the contour lines showed that this was not a simple reversal in the order of the layers, and that the metal layer before and after the displayed “copper” was the same layer. This led to the thinking that, before creating the pattern, some sort of particular process was used so as to reverse the order of the layering in part. Further observation of the C portion confirmed that the layers were reversed with (c) as a boundary and that, furthermore, these were in the same order of layering as the A portion.

It can be assumed from these results that the reversal in the layers is something that happened with regularity. A more detailed analysis of the close-up clearly showed that the reversal in the layers occured alternately as original Mokume Gane patterns in segments of the streamline shape.

The order of the layering was determined to be the 16 layers of copper, Shakudô, gold, copper, Shakudô, silver, copper, Shakudô, gold, copper, Shakudô, silver, copper, Shakudô, gold, copper. It can be supposed that these metals were layered, forged into a billet, and then underwent a twisting process.

The results of the analysis show that after fours counts of twisting of the surface, the back, the surface and the back, the billet was then flattened using a hammer. It is through this process that the twisted pattern that is at the origin of Shoami Denbei’s unique Mokume Gane pattern came up to the surface.

The actual reproduction study was done based on the results of this analysis.

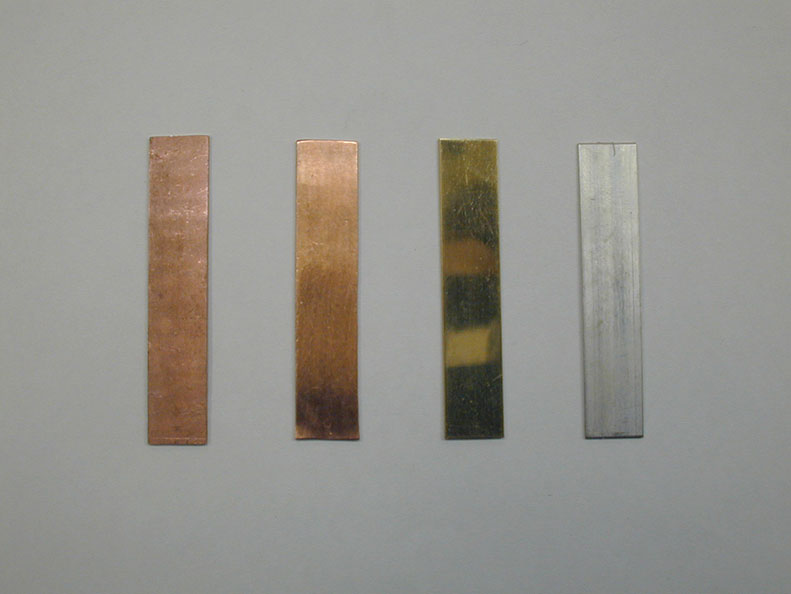

1. Following verification by tracing the pattern, 6 sheets of copper, 5 sheets of Shakudô, 3 sheets of gold and 2 sheets of silver were prepared.

2. The sheets were stacked in order and heated, becoming fused. They were then hammered down in order to produce a rectangular billet.

3. The billet was then slowly and carefully twisted four times, surface, back, surface, back, while paying attention to the order of the layering.

4.The billet that had undergone twist processing was then repeatedly carved and hammered down until it was flat, and the pattern was revealed.

The end of the reproduction study

The thing that very much came to mind at the end of the reproduction study is that these unique patterns are at the root of the original Mokume Gane technique. The point is that this way of revealing patterns goes beyond “something that is produced randomly.” It is the solid manifestation of the culmination of a very refined technique by Shoami Denbei who turned the random into the natural.

Even the patterns that are graceful and fresh at first glance require in their making minute attention and careful work. The reproduction made it possible to experience how the details of the idea that started as a glimmer in the creator’s eye became feasible as a pattern. The insatiable quest of Shoami Denbei for the possibilities in Mokume Gane techniques was clearly felt.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 15

Mokume Gane evolved as one of the techiques in manufacturing tsuba for swords. At Mokumeganeya, we also produce tsuba jewelry that is inspired from the shape of these original sword tsuba. Particularly popular is the tsuba jewelry inspired by the gorgeous ornamentation on the tsuba from the Shôami school.

This chapter will focus on those tsuba as a way of introducing Shôami Denbei, the creator of Mokume Gane, as well as Akita Mokume Gane.

Tsuba

Mokume-Gane Tsuba – unsigned – early Edo period – Shakudo, copper, gold and silver

The tsuba shown here features a four-sided shape known as “Yotsu Mokko” which was quite popular as a tsuba shape during the Edo period. It is reminiscent of a cross –section of a melon with its myriad seeds, it was used as an auspicious shape tied to bountiful progeny. The Mokume Gane pattern, made of gold, silver, shakudo and copper is outstanding in its design. The color combination, coupled with the gold brim, is gorgeous, making it an unusual piece in Mokume Gane where the effect is generally more sober. The design which combines round Mokume Gane spheres within the stripe pattern was achieved using the same methods as for the kozuka (handle fitting for the small sword worn along with the large sword) which is said to be the oldest example of Mokume Gane.

Kozuka

Akita Prefecture designated cultural property – Kozuka – Gold, silver, shakudo, pure copper – signed Shôami Denbei residing in Dewa, Akita

Replica item by Takahashi Masaki

Shôami Denbei (Suzuki Denbei Jukichi 1651-1728) who made this kozuka was the person who invented the concept of Mokume Gane.

The origin of the name “Shôami” lies in the school’s origins in a famous Kyoto family of metalworkers which spread all over Japan during the Edo period. Denbei apprenticed with Shôami in Edo and, after finishing his training, he was employed by the Satake Clan in Akita where he produced numerous outstanding sword fittings. He then founded the Akita Shôami school. Even though the Shôami school expanded widely to Shônai, Aizu, Edo, Bizen, Iyo and Awa, it was the Akita school which prospered most with its new techniques of guribori and Mokume Gane.

Producing the tsuba that is shown here required a pretty large metal base, and the technique to fuse the four different layers of metal without them melting into one another required great skill. Going on to combine three Mokume Gane billets was also a challenging technique yielding an even more intricate pattern. This particular type of gorgeous Mokume Gane that uses a base combining gold, silver, shakudo and copper is categorized as “Akita Mokume Gane” and there are no other cases of a similarly skillful technique and refined elegance.

This tsuba is also featured on the Mokumeganeya website.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 14

From the end of the Bakufu period into the Meiji Era, the foreigners who visited Japan were fascinated by Japanese art and brought many objects back home with them. Many of these were later donated to museums. Mokume Gane pieces are also in the collections of many museums worldwide. Chapters 10 to 13 featured the items in the collections of the British Museum in London and the Ashmolean Museum, the museum of the University of Oxford.

This chapter will feature the Mokume Gane pieces in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London. Mokumeganeya has published “ Textbook of Mokume Gane” through its NPO, the Japan Mokumegane Research Institute.

The publication is a textbook which systematically addresses the history, culture, works, and techniques of the traditional art of Mokume Gane. Many pieces that are featured in the collections of museums overseas, such as the V&A, are included. The opportunity on this visit to see these pieces with our own eyes was a great joy!

The V&A was founded in 1851, the same year as the Great Exhibition was held in London, and the museum opened its doors in 1852, as a museum of decorative arts and design, featuring a collection spanning 5000 years of human creativity from all over the world. Its current palatial home was completed in 1909.

The main entrance of the V&A

The museum’s exhibits cover more than 140 rooms, and it is considered to be world-leading in the quality of its collections and their depth. Just like the British Museum, entrance is free. The inner courtyard which is surrounded by majestic buildings offers a space for relaxation where children can enjoy water games.

The inner courtyard

The design of the exhibition spaces differs according to the contents. Silver items, for example, are displayed in a palace-like setting.

The silver exhibit

In addition to the exhibition spaces in which gorgeous ornaments from Europe’s medieval period are elegantly displayed, the display areas themselves are to be enjoyed.

Precious metals

In the “Japan” exhibition space, the design takes into account Japanese architecture, with the display cases featuring Japanese “Ranma” transoms.

Front view of Japan room

Inside view of Japan room

The lighting in the Japan room is particularly soft, partly to preserve the pieces on show, but also perhaps to show how Japan prizes the beauty of shadows. The exhibit includes displays ranging from the Edo period and Meiji era to modern times, presented in various categories including “tea ceremony”, “lacquer” and “ornaments”

Japan room – 1

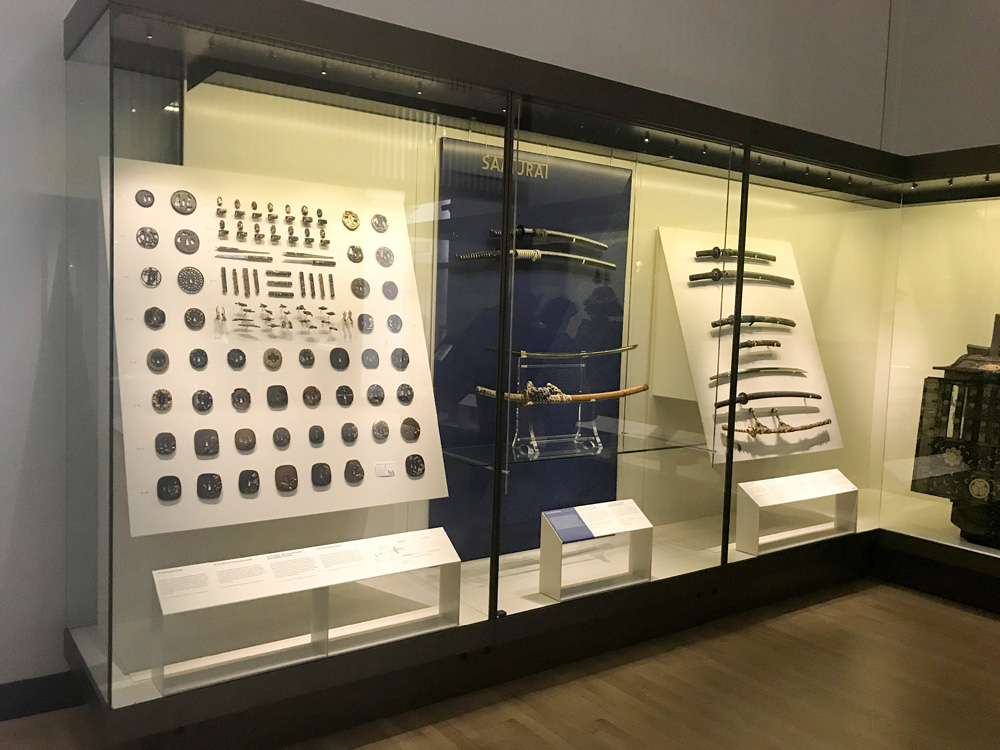

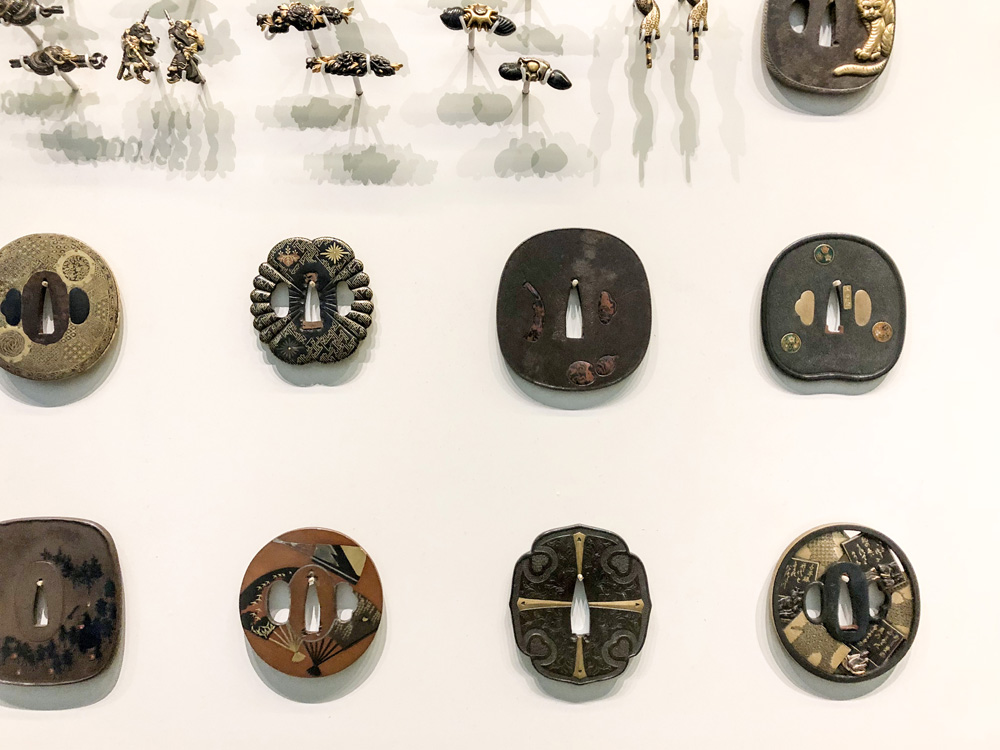

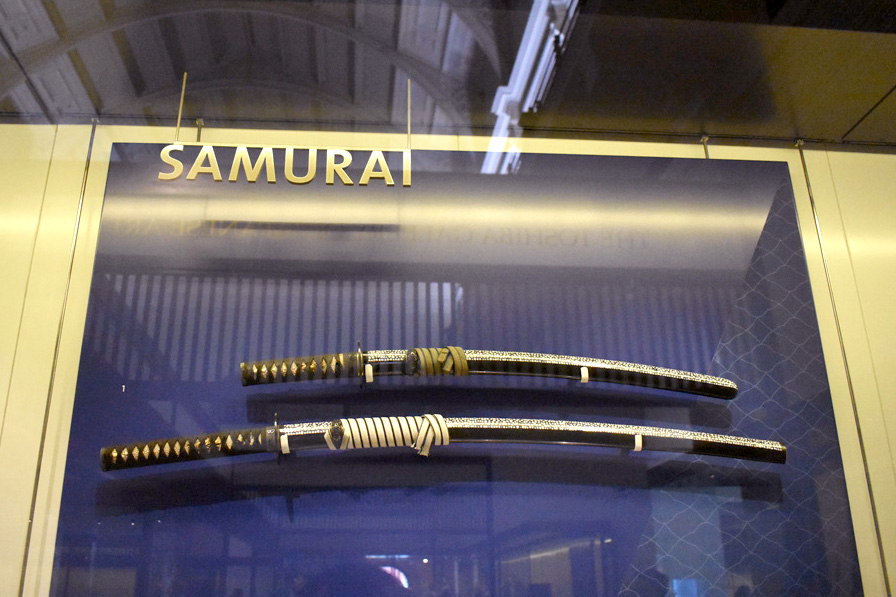

There were many tsuba and swords on display in the “Samurai” corner

Samurai corner

On taking a closer look, there it was, somewhere in the middle! The guribori tsuba signed Takahashi Okitsugu! And there was also a Mokume Gane tsuba.

Guribori tsuba close-up

We have a similar tsuba to the guribori tsuba made by Okitsugu, but in Mokume Gane, in the collection of the Mokumegane Research Institute. Guribori was the technique in which the tsuba makers of the Takahashi School were most skilled. Among them, the carvings by Okitsugu combined both elegance and substance to achieve outstanding solidity. As was shown through the Yoshino River Tsuba in the first chapter of this “Discovering Mokumegane” series, Mokume Gane is not just a technique for making patterns, but was taken to the level of representing images by Okitsugu. One can confidently say that he was also unsurpassed as an expert in crafting guribori.

n the Mokume Gane tsuba, a simple iron substrate has been inlayed with Mokume Gane. Aside from the hitsuana which is the hole through which the Kôgai (the tool that was used for fixing hair) was passed, there is Mokume Gane inlay of a gourd and another, indistinct, long shape. These scattered little accents find a balance in the midst of the large tsuba. With the reverse side of this fun shape featuring a very intricate and challenging Mokume Gane pattern, this item conveys the sense of humor of the craftsmen of the time.

In addition the set of ornaments on the black scabbards for large and small swords that were displayed in the middle, with deep guribori fuchi and kurigata, were doubtless on display to show the quality of the design brought out on the elegantly simple black lacquer finish.

Close-up of large and small swords

And in the corner displaying handicrafts from the end of the Bakufu period, there was a gorgeous Mokume Gane vase.

Vase display close-up

The Textbook of Mokume Gane features a picture of this vase that was provided by the V&A, but it only shows one side of it. On the occasion of this visit, we were able to see the other side at last!

The back

It is a beautiful piece which harmoniously combines highly decorative ornaments in cloisonné, lacquer, mother of pearl and gold inlay, with a Mokume Gane pattern.

As this is a collection which brings together pieces from all over the world from the perspective of decorative arts and design, each and every piece on display in the “Japan” room is exquisite and finely decorated, and one can go on admiring them without ever tiring of them. (Japan room inro)

Looking at sword tsuba, the proportion of pieces made of Mokume Gane within the framework of everything produced by metal craftsmen at the time was very small, but they are featured in the V&A’s display. This helped us realize once again that this is due to their assessment of the beauty and depth that can be seen in the Mokume Gane techniques.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 13

In the previous chapter, we described the pieces that we were able to view during our visit to the Ashmolean Museum, which is the museum of the University of Oxford. There were numerous technically outstanding pieces, such as the tsuba with the three-dimensional chrysanthemum flower pattern. We hope that you were able to get a feel for the beauty of these pieces through the close-up photographs.

The curator of Japanese Art, Dr. Clare Pollard, was kind enough to show us round the storerooms and the exhibition areas also. We would like to focus on these in this chapter.

The storerooms are located in the vicinity of the exhibition areas. In order to preserve the precious pieces so as to transmit them to future generations, it is vital to control the humidity and temperature to protect the pieces from mold and rust, as well as from cracks due to an overly dry environment. For this reason, the pieces are kept separately according to their materials. This is because the ideal temperature and humidity for organic items made of paper or wood and those made of metal are not the same. Even though it would ideally be best to keep tsuba and other sword fittings in separate storage areas from ceramics, they are in fact kept separately in humidity controlled cases.

Cases featuring humidity control labels.

We were not able to visit some of the storeroom areas. Given the sheer number of pieces, Dr. Pollard has not yet been able to catalog everything. The entire collection is not available on the web either, and there may well yet be some undiscovered Mokume Gane pieces, such as fuchi and kashira, among the sword fittings! We left the vaults till later in anticipation of further research.

The Ashmolean Museum features exhibits from all over the world, including a magnificent Japan exhibit.

We mentioned in Chapter 11 that there was a tea ceremony room where tea ceremonies are held once a month. There were explanations on the structure of this tea room on a large panel.

The exquisite construction within a confined space showed off the artistry of the Japanese Sukiya (tea room) construction technique.

Dr. Pollard told us that visitors showed great interest in Japanese culture, and so she made a great effort to provide in-depth explanations of the exhibits. Would they happen to know how an Inro was worn? It was suspended from the obi, using a netsuke to hold it in place. All of this was illustrated so that people could see, with Inro and their netsuke hanging from a bar in the display.

Dr. Pollard also supervises the prints and Japanese paintings and rotates the exhibits once a month. She explained enthusiastically that there is even a corner where visitors can actually take the exhibits into their hands, so that they can familiarize themselves better with Japanese art. After we had spent several hours studying the tsuba, she then graciously guided us through the exhibits until closing time.

This visit helped us understand how much beautiful traditional Japanese artifacts, starting with the Edo period Mokume Gane tsuba, are appreciated and loved by people in other countries.

We at Mokumeganeya will continue our studies on the Mokume Gane pieces that have been handed down from the Edo period, and will strive to continue to transit, not just the pieces themselves, but also these precious techniques.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 12

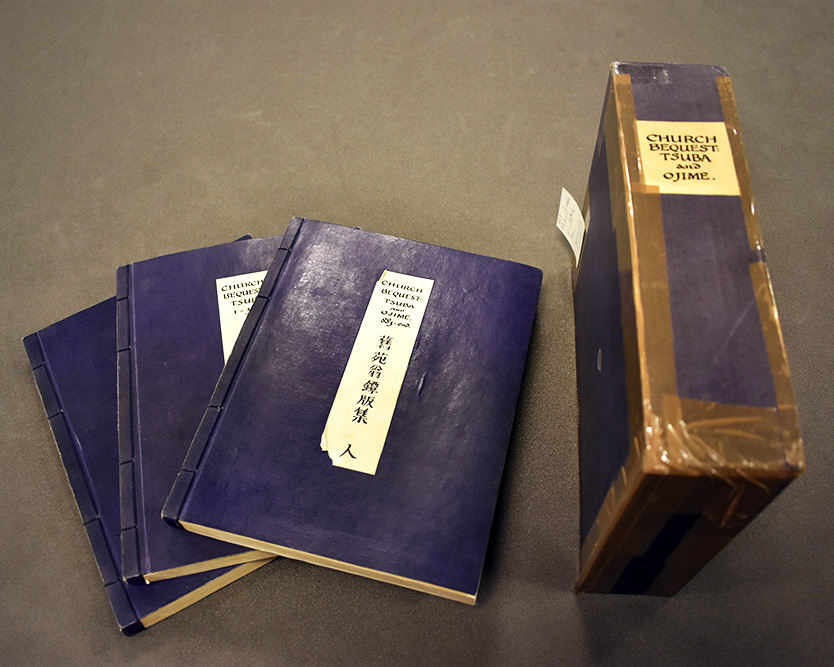

We will continue from our last chapter to tell you more about our visit to study mokume-gane pieces in the collection of the Ashmolean, the museum of the University of Oxford. In addition to the three mokume-gane pieces that were introduced in the previous chapter, the museum also has four guribori tsuba, guribori being considered the origin of mokume-gane.

The museum has a total of 1286 tsuba, including the pieces we studied, in its collection, and the largest portion of 1264 pieces was collected by Sir Arthur H. Church (1834-1915). Born in London, he was a scientist and devoted to collecting Japanese tsuba. In his later years in particular, he collected avidly and was systematic in his approach. As a result, his collection was very complete and his texts on these tsuba have even been translated into Japanese. On this visit, we were also able to view a catalogue of the Sir Arthur H. Church tsuba collection written in 1925 by Albert James Koop (1877-1945). This is a hugely valuable work that has never been published. The contents are in English but were later bound in Japan in the Japanese “watoji” style.

The Ashmolean Museum has an excellent website. The Eastern Art department includes, in addition to the regular collection, detailed explanations based on Koop’s catalogue. According to this, Sir Church was particularly taken with botanical and geometric designs which explains the limited number of pieces depicting people or animals.

This might explain why all of the guribori tsuba he collected were relatively unusual, with very rare pieces depicting chrysanthemum flowers not seen anywhere else.

Although many round or mokkô-shaped guribori tsuba were carved with arabesques, this piece represents a three-dimensional chrysanthemum flower with the 16 petals all carved in guribori.

The lines of the layering make one think of the numerous overlapping petals of a chrysanthemum flower, and the tiny embossed pattern in the hitsuana bring to mind the heart of the flower. Even as a tsuba made for a sword, it looks really quite cute.

This piece is presented as the “chrysanthemum tsuba.” The combination of silver and shakudo is rather modern in appearance, with a very sharp design.

This is a guribori tsuba, but if you look closely, the entire surface of the tsuba is not covered in the arabesque patterns, the free curves are drawn in guribori carving, and the use of the two-color effect of black and red on the surface makes it a very unusual piece that shows an elegant flashiness. Looking at it with our modern eyes, it seems to be a western decorative piece and one wonders what the Edo craftsman had in mind in thinking up this “design.” Isn’t it fun to let your mind wander?

Here is the fourth guribori tsuba. Its round arabesque carvings are of a relatively commonly seen pattern.

The English title for this tsuba is “Tsuba with scrolls” but in Japan, the standard term for “scrolls” or arabesques is “karakusa (palmette) pattern.” This has been used for a very long time as an auspicious decorative pattern showing entwined vine as representing vital force.

In studying these seven mokume-gane and guribori pieces on the occasion of this visit, we spent an entire day taking detailed measurements, examining the various parts closely, taking photos, looking at documentation and visiting the vaults and exhibition halls. Next time, we will tell you about our visit to the vaults and exhibition halls with curator Clare Pollard.

You will find the website of the Eeastern Art department at the Ashmolean museum here:

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 11

In Chapter 10, we told you about our visit to view the Mokume-Gane tsuba at the British Museum in London. We shared the sentiment of those who, a hundred years ago, came across the tsuba in Japan and were moved by their magnificence and beauty. In this chapter, we will tell you about the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford which we also visited on the same trip.

The Ashmolean Museum is located in Oxford which is about an hour by train from London. As you all know, the town of Oxford is where the University of Oxford, a world-class institution on a par with the likes of Harvard University, is located. It has a college system whereby students and teachers live and study within a college, of which there are 39 making up the university. Their buildings are spread across the center of town, boasting gothic architecture going back to the 12th century. The overall impression is of great history and overwhelming beauty.

The Ashmolean is the museum of the University of Oxford. It is the oldest university museum in the world, having been founded in 1683. Its collections are very broad ranging including everything from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. There is also a Japanese collection which even features a tea ceremony room! There is an actual tea ceremony held there once a month, and it always draws a big crowd.

Let us move on to our study of the mokume-gane tsuba in their collection. We had contacted the curator of Japanese art in advance, and we were to view three mokume-gane tsuba and four guribori tsuba. Museum curators in Europe and North America have great academic knowledge, study the items in the collections, and are in charge of planning exhibitions. They are on a par with university professors in Japan.

We were met on the day of our visit by Clare Pollard, the Curator of Japanese Art. Her specialty is Japan’s Meji era crafts but she has broad knowledge of Japanese art as a whole. She was a delightful, smiling lady who spoke Japanese and had conducted her own research at the Tokyo National Museum in the autumn of 2000. In addition to showing us the tsuba that day, she also took us around the vaults and exhibition halls, and we ended up spending an entire day there.

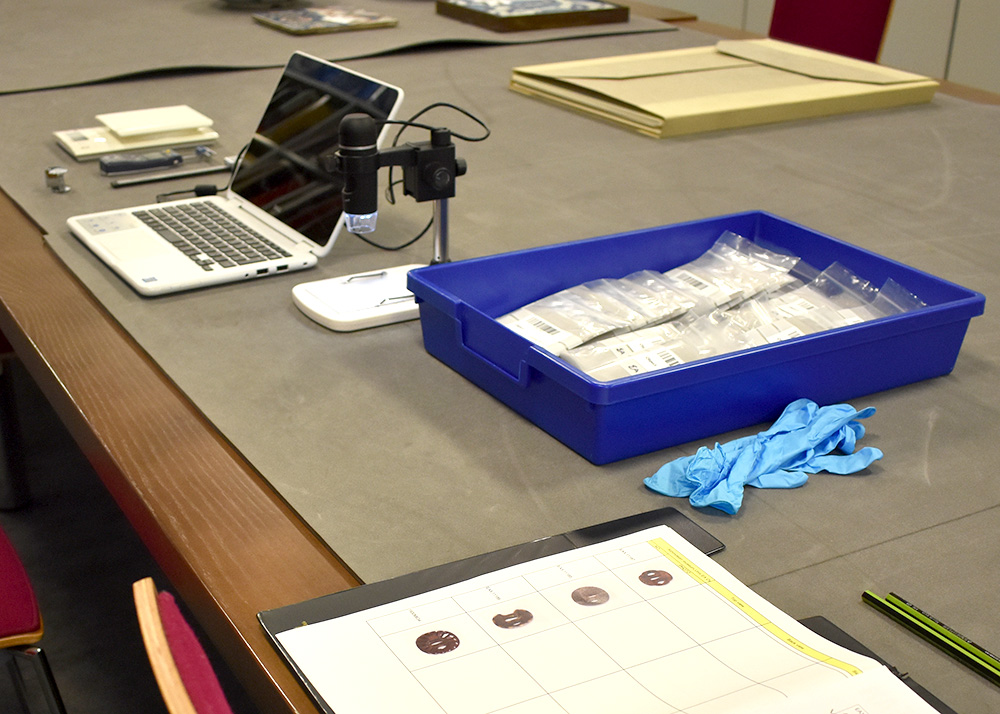

The various pieces were laid out on a table covered in felt and a layer of silk paper to avoid scratches, as had been the case at the British Museum.

We were finally in the presence of the actual pieces and started examining them and taking measurements. We began with the three mokume-gane pieces.

This is a rather small mokkô-shaped tsuba. It was probably for a small sword. The color on the tsuba is outstanding with a bright red copper achieved by niiro-chakushoku with copper sulfate. The other color is black shakudo (a combination of silver and copper). The beautiful mokume-gane pattern carved out on a small surface makes it a very interesting piece.

A large tsuba covered in countless round wood grains. It alone weighs 123.5 grams, hinting at a pretty heavy sword overall. It is very similar to a tsuba in the collection of the Baur Foundation Museum in Switerland.

This is a highly unusual decorative tsuba. It is a tsuba that required a great deal of work, with the main mokume-gane part in three colors to which another metal was affixed, and the rim of the fuchi also being in three colors. One can but wonder about the dandyish samurai who owned it, and his flamboyant taste!

The time just flew by as we examined the pieces, measured them and took detailed photos.

We will tell you about the four guribori pieces and visiting the exhibition halls in the next chapter!

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 10

Mokume Gane pieces such as sword guards have been collected as works of art by foreign collectors since the Meiji era. Many of these are now part of the collections of the world’s great museums. On this occasion, we would like to tell you about the Mokume Gane pieces which are part of the collections of the British Museum in London and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

The British Museum is located in London, England, and boasts the largest number of collection pieces of any museum in the world. It holds about eight million pieces, including many excavated artifacts and works of art that were collected during the heyday of the British Empire in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Many famous cultural assets and works of art are on display including the Rosetta Stone which played a major role in the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphics, as well as ancient Egyptian mummies and a Moai from Easter Island.

The Mokume Gane pieces which we determined to be in the collections of the British Museum are not normally on display but are kept in the storage vaults. These pieces came to be part of the British Museum collections upon the death of Collingwood Ingram (1881-1981). He was an ornithologist and also a plant collector. During Queen Victoria’s reign, in the second half of the 19th century, he brought back many ornamental cherry trees from Japan and their beauty led to a boom. Mr. Ingram visited Japan three times, collecting Japanese cherry trees, a subject on which he became a global authority to the extent that his nickname was “Cherry”. So, he had a deep connection with Japan and became a great collector, particularly of netsuke, but also acquired Mokume Gane tsuba. It is possible that we were the first Japanese in almost a century who were able to admire these items that had crossed the ocean along with cherry trees.

We conducted this visit after obtaining permission from the Department of Asia for people from the Mokumegane Research Institute to come to England for a study visit. On the day we visited in mid-June, there were already many people gathered in front of the main entrance before opening time. Visits to the British Museum are free for people from all over the world, and there are boxes for donations. Much of the cost for the upkeep and exhibition of these precious objects comes from donations. We also made a contribution and then immediately headed to the designated place for our research at opening time.

We were a little nervous when we knocked on the door of the research department which is located beside the Asian art exhibition halls, but we were welcomed with a smiling face by Daryl Tappin. She is an assistant collections manager in care and access for the British Museum collections. She explained to us the outline of the warehouse and preservation methods, and she also gave us some details on other museums in Britain with Japanese collections. She was most kind and the day proved very useful to our research.

The table was entirely covered with felt so as not to damage any of the items, and there was a further layer of fine paper on top of the felt. There was a digital microscope and measuring instruments had also been brought in for us. We put on the rubber gloves that had been provided and started our research.

A sword tsuba made of Mokume Gane had already been displayed on a broad study table. There was one Mokume Gane tsuba as well as a tsuba with decorations similar to Mokume Gane. We experienced a moment of delight on seeing for real the Mokume Gane tsuba which we had only see through images on the web!

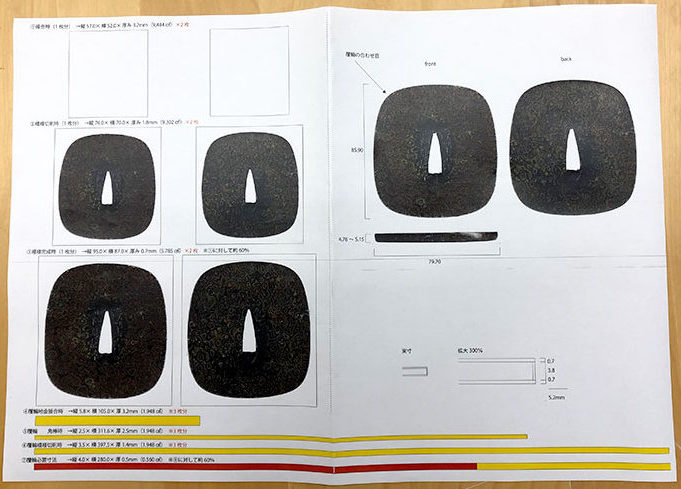

We were finally able to pick up the tsuba and take detailed measurements of its size and weight. Many tsuba appear flat at first sight but they are made so that the central part is thicker, the thickness and hitsuana are measured radially in a total of 24 spots from the center of the tsuba to the rim. Every part was also photographed using the digital microscope.

As a result of this, we made discoveries that had not been apparent from just looking at web photos! It is often the case that the fuchi portion of the surface and side of the back and front of the tsuba are made separately, but with this tsuba, the Mokume Gane sheet for the surface was worked, as is, for the fuchi too. You can probably see from the illustration how the Mokume Gane pattern continues on to the sides. It requires extraordinary technical skill to create the fuchi as though it had been wound subsequently, from one same sheet without breaking the Mokume Gane pattern.

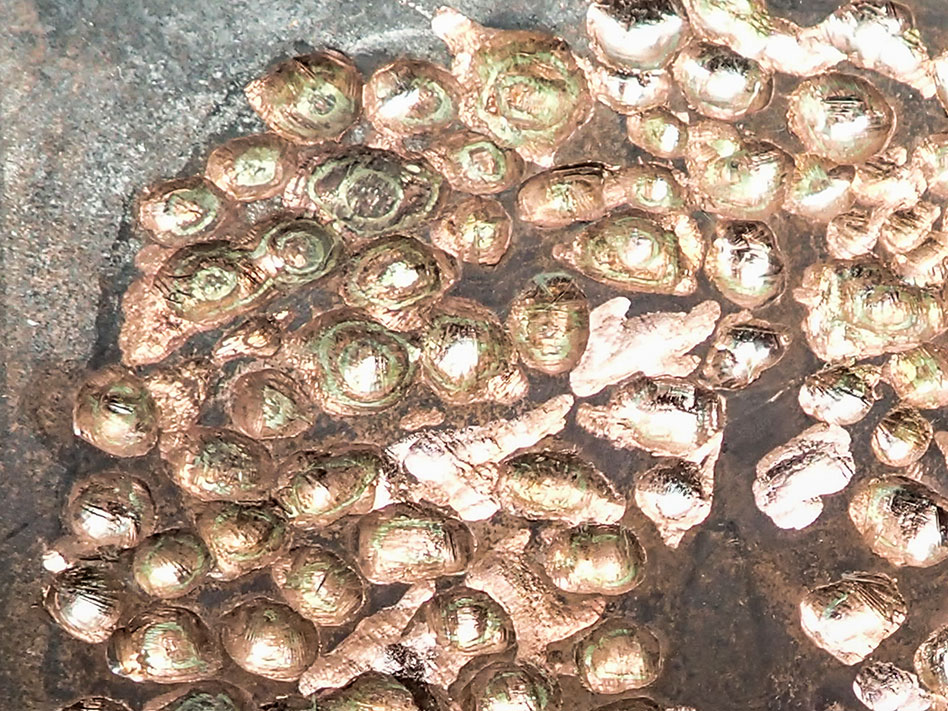

In addition, what looks like flea-bitten traces on the surface and back of the tsuba was in fact produced by hammering a steel mold on top of the Mokume Gane sheet. This can be deduced from the way the Mokume Gane patterns is continuous. Furthermore, the inside of the molded pattern was decorated using a chisel with an indented tip called a nanako. Through close examination on this occasion, we were able to understand how the changes in the various types of flea-bitten traces were achieved by combining different sizes of mold, and admired this outstanding manufacturing technique.

Mr. Ingram who brought this tsuba to England was an ornithologist and a botanist. It is likely that he admired the delicate skill of the Japanese in showing nature, such as the patterns made with Mokume Gane and the flea-bitten expressions, and fell in love with them. Through our examination, we felt once again how truly outstanding pieces go beyond time and borders, in spanning the centuries.

At the Ashmolean Museum that we also visited in Oxford on this trip, there were seven Mokume Gane and guribori tsuba. All of them were extremely interesting, and they included decorative techniques that are not to be seen elsewhere. As the person in charge of Japanese art also showed us relevant documents and vaults, we will share details of these in further chapters!

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 9

Each year, our president, Masaki TAKAHASHI undertakes the reproduction study of an Edo period Mokume Gane piece. His quest, as he does this, is to see how the craftsmen of the time used Mokume Gane techniques to produce their works, and what their frame of mind was as they did so. As he looks at the name of the craftsman of the period inscribed on a sword tsuba, he delves into the relationship between the craftsman and the technique of Mokume Gane as he attempts to reproduce both technique and expression.

In this chapter, we will introduce the process of such a reproduction study so that readers can get something of a feel for the process.

This particular reproduction is of a mid to late Edo period piece signed Shoami Moriaki, residing in Yoshu Matsuyama.

This is the work of the Iyo Shoami school which was located in modern-day Matsuyama, in Ehime Prefecture. Those of you who are familiar with Mokume Gane will doubtless recognize the Shoami name. This is the very same Shoami as in Shoami Denbei who manufactured the kozuka which is considered to be the oldest piece of Mokume Gane. This was a renowned name among metal craftsmen. This school sprang up in the late Muromachi period as metal and tsuba craftsmen, and eventually split into more than 20 branches, including in Kyoto, Iyo, Awa, Aizu, Shonai and Akita. Shoami Katsuyoshi was also famous in the late Bakufu and Meiji periods.

This tsuba by Shoami Moriaki is rather large within the framework of sword tsuba. The shape of the tsuba is descrtibed as “saddle flap” (aorigata), with the width of the lower part rather wider than that of the upper part, giving it a stable shape. Saddle flaps are part of a horse’s equipment and were leather flaps that would be placed on the horses’ body to protect them from mud. Warriors would be familiar with that shape which is why the expression was also used for tsuba shapes. There are also various other tsuba shapes such as fan-shaped (gunbaigata) and quince shaped (bokegata). We will introduce these on another occasion.

Let’s take a closer look at this tsuba’s Mokume Gane pattern. There is an intricate patterns that covers the entire surface of the tsuba. Could it be the light of the moon at night or perhaps sunshine filtering through foliage reflecting on a gently flowing river, a hard to define, ever-changing pattern. The large and small round burls, known as tamamoku, covering the entire surface, seem to be connecting the drift of the river flow. With copper, shakudo and silver as materials, the landscape is one of interweaving vermillion, black and silver, giving the effect of algae and rocks at the river bottom being visible through the water surface.

That is the concrete landscape and image that the artist wanted to show. In order to do this, he used Mokume Gane techniques, so that Mokume Gane played nothing more than a supporting role to the artist. If one looks back over the history of Mokume Gane tsuba, the Shoami Denbei kozuka that was mentioned earlier, as well as the tsuba made by Morikuni of the Iyo Shoami school, the older the work the more detailed the pattern and the greater use of Mokume Gane as a technique to bring to life the landscapes and views of the world that the artists wanted to show in the tsuba.

Kozuka by Shoami Denbei

Tsuba by Morikuni of the Iyo Shoami school

The years went by and, looking at the tsuba of the late Edo period, they are mostly made of fixed patterns. The boar-eye (inomegata) polished Mokume Gane tsuba such as the one signed Masataka is such an example.

Boar-eye polished Mokume Gata tsuba signed Masataka

The extremely detailed and intricate patterns requires high-level technique, but the pattern of the design is achieved by steady carving in a prescribed fashion. The Mokume Gane technique is entirely being used as the technique to carve the pattern. It was probably standardized with efficiency and productivity in mind. Of course, everyone recognizes it as a piece that embodies Mokume Gane techniques in bringing to life a beautiful pattern. But the technique of Mokume Gane can go beyond that to show something deeper.

This piece by Moriaki is very much in the style of the Iyo Shoami school, looking at first glance like a design that has been made into a pattern, but you can see the traces of how the artist in Moriaki elaborately created the landscape that he wanted to draw.

In carrying out reproduction studies, examination of this type of tsuba leads to imagining the feelings and the aim of the artist, and the manufacturing process is carried out with that same image in mind.

The first step was to determine the metals used from their color, and finding out in which order the various metals were stacked. The pattern that appears to be a flat surface is broken down to its levels by sight, and it is not easy to determine that order correctly in cases where there has been repeated carving and flattening. The next step is to take measurements of the tsuba. Data is obtained on the number of sheets and the thickness of each metal sheet that make up the pattern. This analysis is so that the pattern can be carved initially in a tsuba mold that is smaller than the finished product so that when the final product is flattened and stretched, it is the same size as the original.

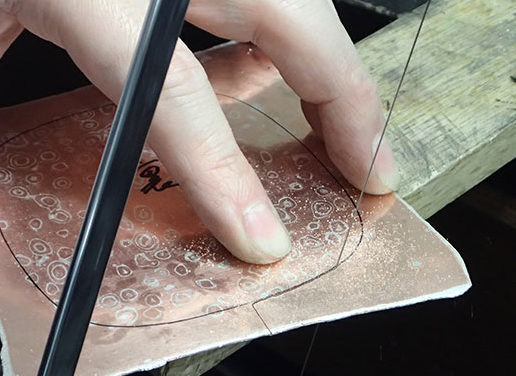

The next step is to copy the pattern onto tracing paper from an image that has been reduced from the original tsuba image, and the pattern is then copied on to the metal billet that has been prepared. The billet is made from stacking metal sheets of the thickness that was determined earlier and heat bonding them.

A circular shape is the first thing to be carved. The carving is done carefully while observing the size of the pattern and how the layers appear in the original tsuba. This is because, depending on the depth of the carving and its angle, the color and surface of the pattern will look different on flattening.

Once the carving is complete, the tsuba is heated and the repetitive job of stretching it to the size of the original is undertaken. The pattern is complete when the surface is quite flat. It is then cut to the shape of the original tsuba.

Once the carving is complete, the tsuba is heated and the repetitive job of stretching it to the size of the original is undertaken. The pattern is complete when the surface is quite flat. It is then cut to the shape of the original tsuba.

The tsuba which was reproduced on this occasion is if the “fukurin” type in which the outer circumference is also made of Mokume Gane. A long and thin billet is carved in the same way, and then stretched flat, and then wound around the edge of the central part of the tsuba.

The front and back of the tsuba are both covered in Mokume Gane and the last thing to be done, depending on the shape of the tsuba, is to inscribe the signature.

The final process for finishing consists of niiro process patination. We will tell you about patination on another occasion but there is a process of soaking in grated daikon radish before boiling in copper sulfate that was a must in the past and is still so today.

There is absolutely no magic in any of this as it is a chemical process that gives a delipidization effect, but it is not quite comprehensible, even in this day and age.

The niiro patination time will vary according to the materials used. The changes in color should be checked from time to time, and care is taken to avoid contact with air.

On completing the reproduction project, what is felt is how the artist used Mokume Gane techniques to bring to life a certain kind of landscape. It is not a collection of patterns that were carved at random but the elaborate manifestation within a tsuba of an image clearly held in the eye of the artist using the attributed of Mokume Gane.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 8

In the Mokume Gane Textbook that was edited by our president, Masaki TAKAHASHI, there are also some works of MOKUME GANE made by overseas artists.

James Binnion is one of those artists. He has been studying Mokume Gane independently in the United States for over 30 years.

He was featured in a recent TV program entitled “Sekai! Nippon Yukitai Jin Oendan” (The World! Cheering on those who want to go to Japan!), and the Japan Mokumegane Research Institute, of which Masaki TAKAHASHI is director, fully cooperated with the recording. On the day of the recording, the cherry blossoms were in full bloom under a perfect blue sky. Mr. Binnion, who was visiting Japan for the second time, and his wife, were impressed by the beauty of Japan’s nature.

Mr. Binnion had only ever seen one original example of Mokume Gane, the products that had been born of the techniques of the Edo period, and that was the Yoshino River Tsuba at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He was able to see many Mokume Gane pieces during this visit and so enjoyed his trip to Japan a great deal.

On the day of the recording, the first item to be introduced was a sword with Mokume Gane fittings which he picked up and examined with great interest, and he even held it to his side in Samurai fashion.

The piece itself is extremely rare in that the elements such as the fuchi, kashira, kawaragane and kojiri are made of the same Mokume Gane pattern and have been preserved along with the sword’s sheath. Also, the tsuba dates from the latter part of the Edo period and is signed Shoami Morikuni, residing in Matuyama, Iyo province, made of Bombay Black Wood (Tagayasan). It is an unusual four square pattern Mokume Gane.

Takahashi went through the history of Mokume gane, starting with the guribori works which were at the origin of Mokume gane and going through to Edo period pieces.

The pieces viewed were not just tsuba, but included items such as yatate and kettles, and both Binnion and Takahashi, as Mokume Gane artists themselves, marveled at the skill of these craftsmen, and both felt the scale of the challenge in pursuing these techniques.

The difficulty in bonding stacks of different metals and then, after the further process of creating the pattern, the great skill required to form a three-dimensional object. On seeing for himself a variety of Edo period pieces with different patterns, Binnion was able to get something of a feel for the creative process of people in ancient times. Mr. Binnion has devoted most of his life to producing Mokume Gane. After seeing part of the collection on this visit, he was delighted and expressed the intention of coming for a return visit.

On the same day, there was also a separate filming of collection items, with detailed close-ups of Mokume Gane patterns which was most interesting, as the actual images doubtless will be. Please make sure to catch it on television.

The program was aired on Monday, April 23, on TV Tokyo group channels.

The website for the program (Japanese only) is at: http///www.tv-tokyo.co.jp/nipponikitaihito/