Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 7

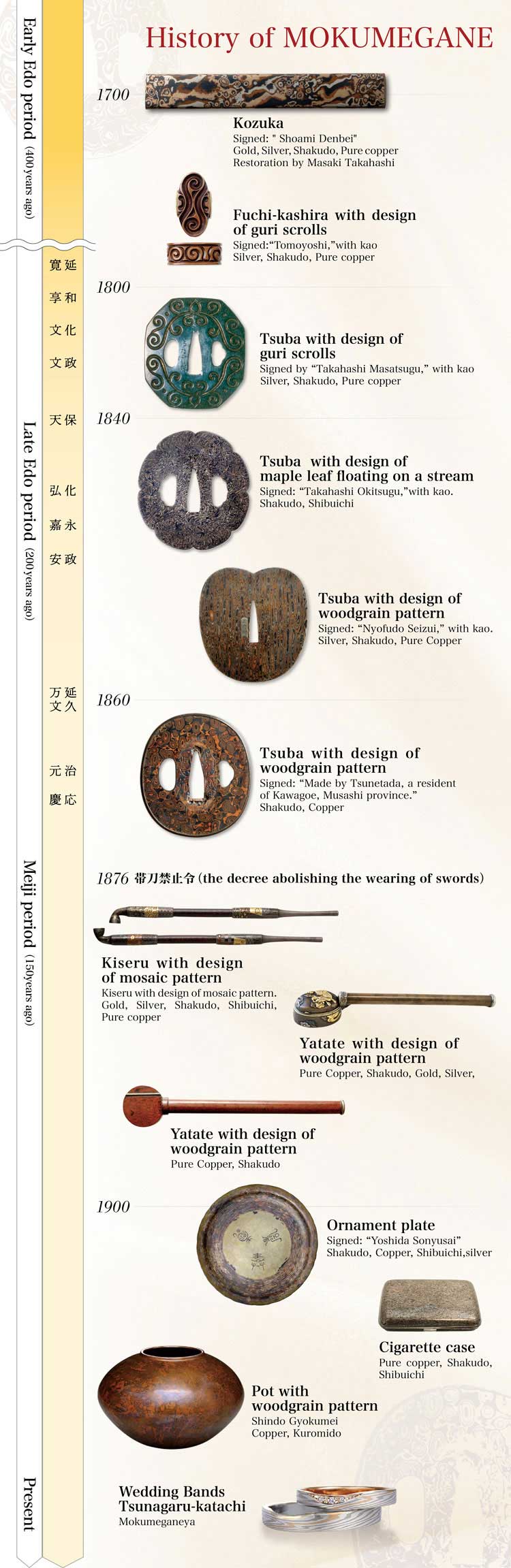

In the previous chapter, we introduced our research and studies concerning Mokume Gane pieces both in Japan and overseas. In this chapter, we would like to tell you about the history of Mokume Gane with an emphasis on Japan’s metal craft as it related to personal accessories.

The Origins of Jewelry in Japan

The origins of jewelry are said to go back to the Paleolithic age, about 12,000 years ago. The evolution was from objects made of stone to those made of bone, shells and wood, as seen in the Jômon period. In those days, it was not so much a question of elegance. Rather, they were used as symbols of authority, or in festivals, or as signs of belonging to a clan, and so evolved very much as tools with a strongly social significance. From the Yayoi period onward, glass, gold, silver and gilt bronze were added to the mix but jewelry continued to circulate, not as ornaments, but having powerful political or religious overtones.

Metal Craft Progressed Apace With Sword Making

In later periods, various crafts were also introduced from the continent, and developed apace with changes in people’s customs and patterns, playing a major role in forging Japanese culture. In particular, it was metal craft that developed independently with the advent of a warrior society in which the sword symbolized the spirit of the warrior. And it was over the 250 years of peace during the Edo period that the art of Japanese metal craft truly flourished. With fewer armed conflicts during the Edo period, the sword went from being a weapon of war to a thing of beauty that was used as an ornament.

The oldest piece of Mokume gane in existence is a kozuka (the handle of a small knife)*1 made by Shoami Denbei, residing in Dewa Akita. It is outstanding by the elegance that comes from the combination of gold, silver, copper and shakudo.

The Development of Personal Accessories During the Edo Period

The techniques for manufacturing personal accessories developed during this period of peace which saw changes in the warrior society as well as the flowering of the merchant culture. The use of these items, starting with kiseru, inro and netsuke, became widespread among warriors and merchants alike. Everyone is now familiar with the typical scenes of merchants with an inro looped around their belt and smoking kiseru that are so common in period dramas. Much effort was put into coordinating the various items, and pieces have come down to us showing the particular humor of the merchant culture that combined the chic and the amusing. Mokume Gane also came to be used in daily accessories such as kiseru and yatate (portable writing boxes) *2. A variety of metal working techniques that had been honed in sword-making, such as the technique of sawing, or openwork, inlay that inserts different colored metals, just as in marquetry, were liberally used.

Changes in Metal Craft Techniques

in the Meiji and Pre-Modern Era

Times, however changed dramatically with the advent of western culture during the Meiji era, and in the 9th year of Meiji (1877) the law forbidding the wearing of swords was passed. The craftsmen who had made a living as swordsmiths turned to making hanging personal accessories or were encouraged to produce pieces for export to make a living. The techniques of Mokume Gane died out for a time following the Haitôrei Edict (prohibiting the wearing of swords) and even came to be known as the “ghost techniques,” but the later enthusiasm and efforts of modern aficionados successfully revived them.

At Mokumeganeya, we have been making a systematic effort to collect, preserve and study the precious techniques of Mokume Gane. We have also overseen the compilation of the Mokume Gane Textbook, and are working to distribute it widely.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 6

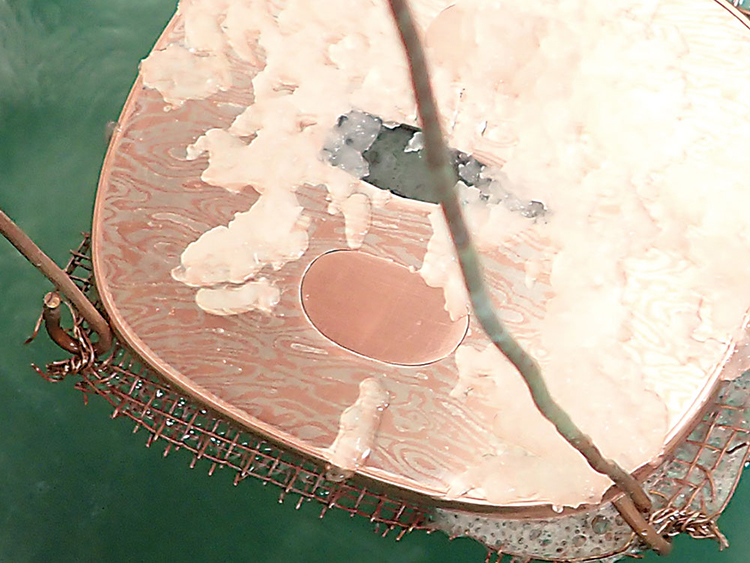

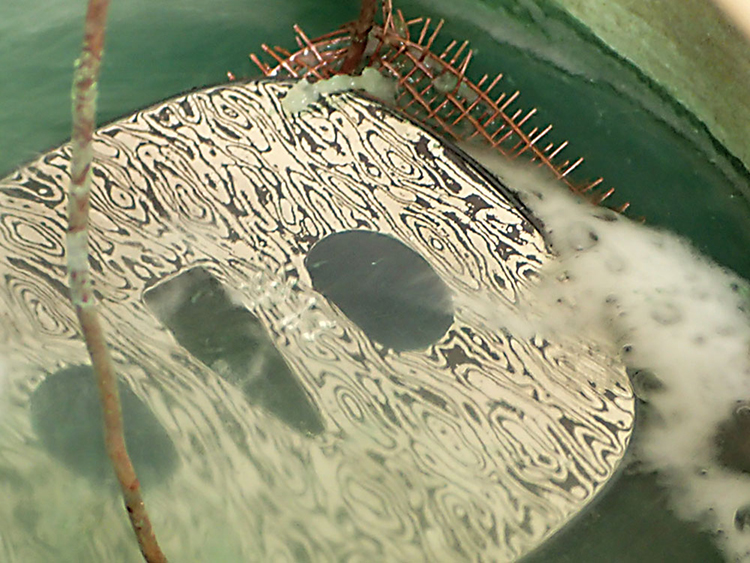

At Mokumeganeya, each year, we work on the reproduction of a famous sword tsuba. The work that was presented in April 2017 at the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords’ Shinsakuto (newly made swords) exhibition, is a reproduction of a Meiji era work “Mokume Gane tsuba, signed Toshinobu, residing in Matsuyama.” Following the win in the “Effort Prize” category for the 2015 reproduction of the tsuba from the Baur Foundation Museum of Far Eastern Art in Switzerland, this reproduction was also awarded the same prize.

Reproduction by TAKAHASHI Masaki of Mokume Gane tsuba, signed Toshinobu, residing in Matsuyama

The tsuba which was reproduced on this occasion is the property of the NPO, Japan Mokumegane Research Institute. It is a piece made by YAMAMOTO Toshinobu in Matsuyama, Iyo Province (the current Ehime Prefecture), during the Meiji era. It is an extremely important piece as it is a two-sided Mokume Gane tsuba that is part of the koshirae for a long and short sword. The front and back of the tsuba represent “night” and “day.” They seem to be somewhere between the realistic and impressionistic, and offer an artistic representation of “night and day.”

“Mokume Gane tsuba, signed Toshinobu, residing in Matsuyama”

Collection of the Japan Mokumegane Research Institute

The materials used on the “night” surface are shakudo and silver. Shakudo is an alloy made of copper and gold and, at first sight, appears no different in color from pure copper, but the chemical boiling bath patination process turns it a bluish black. The back “day” side is made of shakudo and pure copper. The patination of the pure copper turns it a reddish brown.

Front – Before Patination

Front – After Patination

The chemical boiling bath patination consists of boiling for a period lasting from several dozen minutes to several hours in a mixture with cupric sulfate and rokusho, leading to oxidation of the surface and an associated change in color. Deliberate oxidation of metals to achieve desired colors is an age-old patination process, and pieces such as the Meiji era “Night and Day” have survived over a hundred years with their beautiful color unchanged.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 5

During the late Edo period, sword craftsmen also put their hand to manufacturing everyday utensils used by townspeople such as portable writing sets (yatate) and smoking pipes (kiseru). Mokume Gane was also widely used in design during the Edo period. There are also numerous Mokume Gane works that were produced during the Meiji era for export or as souvenirs. This chapter introduces some such pieces from our collection. Please enjoy seeing some products other than the Mokume Gane sword tsuba that you are all familiar with.

1. Guri Incense Container

Ming dynasty China Lacquer

Height 37.7mm

Diameter 70.2mm

This piece is particularly decorative even among guribori works.

* Incense containers are used to store incense. These are used during the tea ceremony.

2. Small Metal Kettle

Late Edo period Shakudo, Copper

Height 60mm

Width 70mm

A cute small kettle

Entirely made of Mokume Gane, apart from the knob on the lid.

3. Yatate (portable writing set)

Late Edo period Shakudo, Copper

Length 210m

A Yatate was a portable writing set. Its small ink container made it possible to write with a brush when away from home.

Entirely covered in Mokume Hane. Even though it is standard in shape, the use of Mokume Gane gives it a natural feel.

4. Tonkotsu (Tobacco Box) With Netsuke

Late Edo period Lacquer

Tobacco Box:

Height: 87.5mm

Width: 76.5mm

Netsuke:

Height: 25.1mm

Width: 43mm

This is a very rare guribori tobacco box. Tonkotsu were used to carry tobacco. The origin of the name “Tonkotsu” remains unclear

5. Tonkotsu With Kiseru Pipe Holder

Late Edo period or early Meiji Era

Tonkotsu:

Height: 73mm

Width: 84.3mm

These are very unusual lacquer items depicting Gigaku masks

These rare pieces are the product of the culmination of guribori design. They are thought to be specially commissioned pieces ordered by an amateur who was a real dandy.

6. Kiseru pipes with a mosaic pattern

Mid to late Edo period

Gold, silver, shakudo, shibuichi, copper

Top:

Length: 270mm

Bottom:

230mm

Two types of pipe that were made using Mokume Gane, damascening, inlaying, and carving techniques to give the effect of metal marquetry. Both the color combinations and colors are modern, giving them an air of glorious gracefulness.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 4

After winning the Good Design Award in 2015, “Tsunagaru Katachi” (linked shapes) went on to receive a Red Dot design award in 2016, one of the three most prestigious product design awards in the world.

Presentation of the awards ceremony

Presentation of the awards ceremony

There were 5,214 entries from 52 countries for the 2016 Red Dot design awards, with 1304 winners. Major global companies such as Apple, Nike and Dyson have been frequent recipients of the award in the past. Winners from around the world gathered at the awards ceremony. The winning products, including the “Tsunagaru Katachi” wedding rings, were on display at the Red Dot Museum which is housed in the redesigned decommissioned Zeche Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in Essen, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Red Dot Design Awards 2016 – Winner

“Tsunagaru Katachi” wedding rings

On the occasion of attending this award ceremony, we also visited Germany’s Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (museum of fine, applied and decorative arts). Hamburg is Germany’s second largest city, after Berlin. The central theme of the museum, which has a 140 year history, is to be a “museum for arts and industry.” The museum has an ongoing perspective on design as it has evolved apace with technology.

Hamburg’s Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

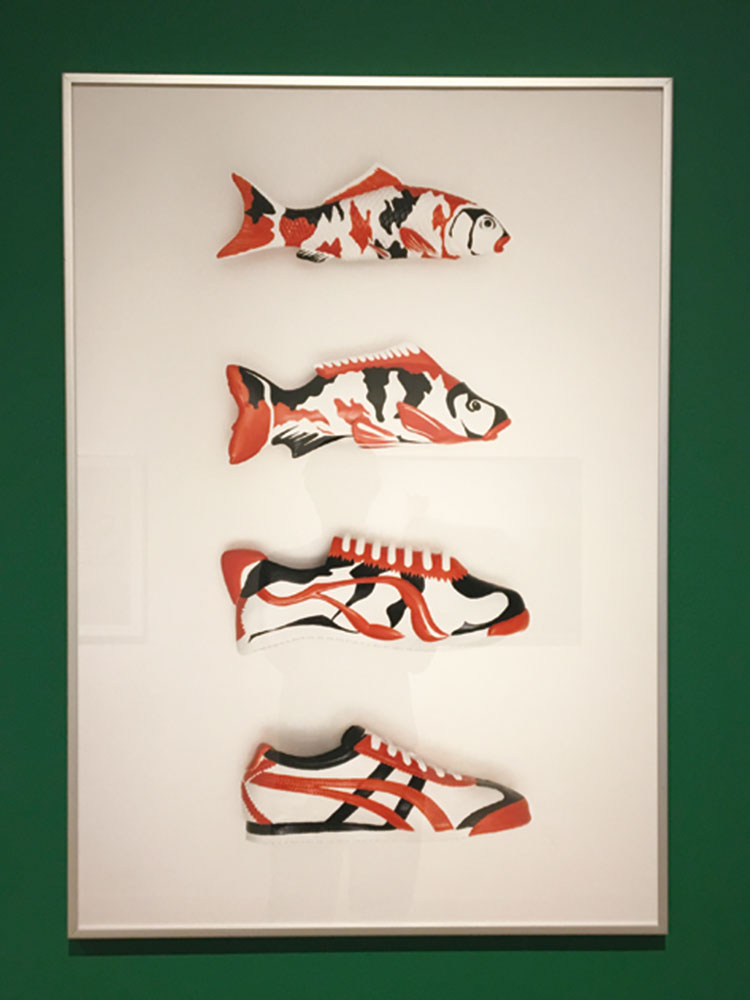

The museum’s approach is to display old and new art and design under the same roof, for the benefit of today’s artists and crafts people. At the time of our visit, there were exhibitions of Nike shoe design as well as Hokusai’s “Manga.”

The Nike Shoe design Exhibition

The Nike Shoe design Exhibition

The permanent exhibition is modern in feel

The permanent exhibition is modern in feel

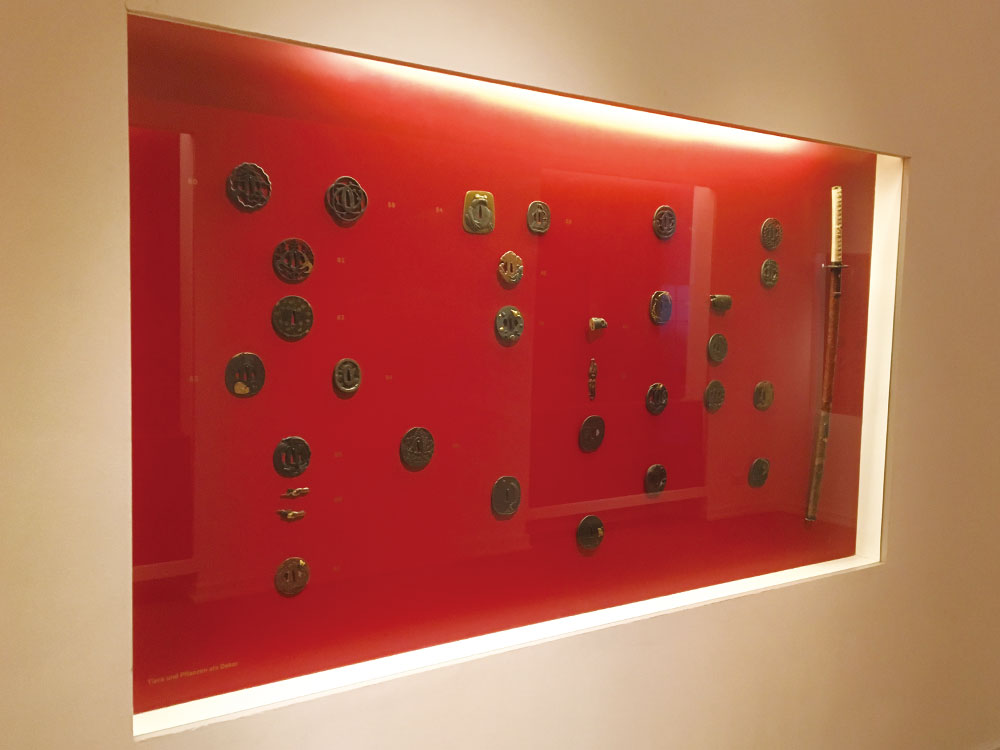

The aim of this trip was to visit the museum’s far eastern collection. There were many swords and tsuba on display, and there was also a tea ceremony room.

The permanent exhibition of Japanese works

The permanent exhibition of Japanese works

The museum has one of the world’s leading collections of art nouveau, which was heavily influenced by Japonisme, reflecting its direction. Guribori pieces are on show in the Far Eastern portion. These are the lacquer guribori works that are at the origin of Mokume Gane.

The feeling from seeing the combination of eastern and western, of old and new, in this museum was very much in the spirit of “Tsunagaru Katachi” (linked shapes). It is the power of present-day works that are the result of the fusion of tradition and innovation. Mokumeganeya will continue to adopt this approach in what it makes.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 3

Every year, we at Moukmeganeya reproduce a famous Edo period tsuba and enter it in the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords’ Shinsakuto (newly made swords) exhibition. Our reproduction entry for 2015 was featured in the “Bi no Tsubo” (Pot of Beauty) program on NHK national television in January 2016.

Reproduction of Wakashima Mokume Gane Ji-Tsuba

Signed: Masamichi, resident of Kofu

Later part of the Edo Period – Shakudo/copper

Signed Masaki

The tsuba that is the subject of this essay is part of the collection at the Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen, and was examined by us in the spring of 2015. The museum has a fine collection that covers not just Denmark’s history from the Middle Ages to modern times, including works by famed Danish designers such as Arne Jacobsen and Hans J. Wegner, but also includes a large international collection.

The museum, which has in its possession a large number of other tsuba from the Edo period, gave us special access to its storage facility during our visit, so that we could examine the Mokume Gane masterpiece. There are several photographs of this tsuba, obtained with the cooperation of the museum, in our book, “The Mokume Gane Textbook.”

Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen – Mokueme Gane Collection (1)

Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen – Mokueme Gane Collection (1)

Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen – Mokueme Gane Collection (2)

Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen – Mokueme Gane Collection (2)

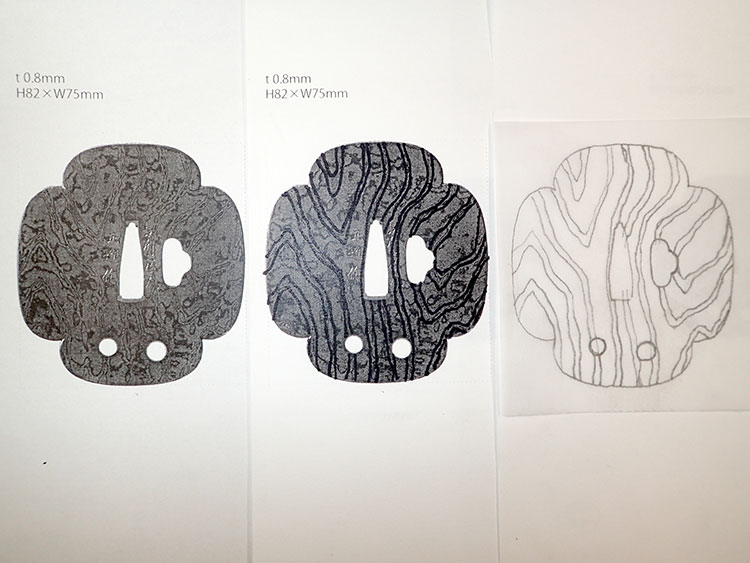

The particularity of the tsuba that was reproduced on this occasion lies in the intricate curves that seem to flow. The pattern is unusual in Mokume Gane, with the speckling that seems to expand and flow. Randomness plays a major part in creating Mokume Gane patterns, but this kind of pattern cannot be achieved without planning and effort on the part of the craftsman.

Layout

Analysis of Mokume Gane pattern

Reproduction Study

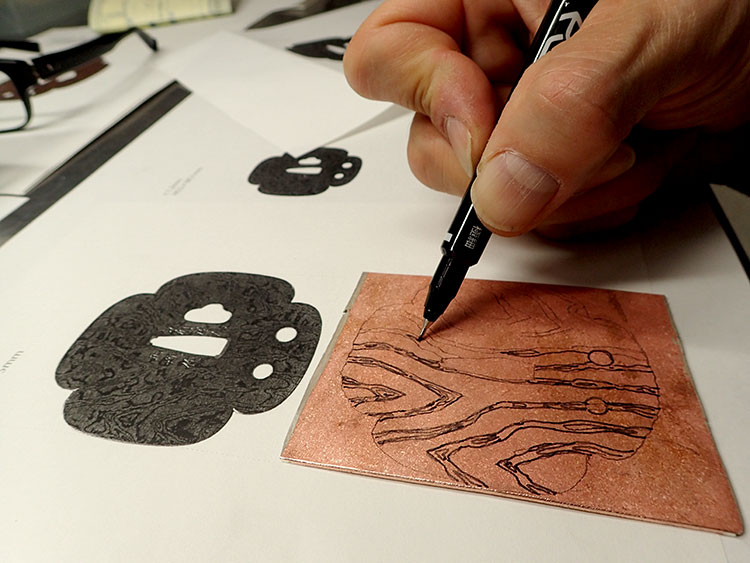

The first step in transcribing the pattern so as to make the pattern on the base metal

Carving out the pattern using a Tagane chisel

Within the framework of this reproduction study, it was very important to conduct the proper analysis to reproduce this pattern, and great care was needed in the carving work to create the pattern. The delicate and lovely Mokume Gane that is represented in the confined world of the tsuba speaks of outstanding technique. Even in Denmark, a country known for its design, people are doubtless captivated by it.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 2 Part2

In the first part of this chapter, we talked about the connection between Mokumeganeya president TAKAHASHI Masaki and the tsuba by TAKAHASHI Okitsugu which is at the Boston Museum of Fine arts. On returning to Japan after studying the Yoshino River tsuba which had traveled all the way to that museum, TAKAHASHI Masaki decided to make a reproduction of it. This chapter will introduce this reproduction process.

The greatest characteristic of both the Yoshino River and Tatsuta River tsuba is their totally unique concrete representation of cherry blossom flowers and red maple leaves using Mokume Gane. In Mokume Gane, tools such as “Tagane” chisels are used to carve the multi-layered material, with the designs being produced by obtaining color through a hammering process in which lower metal layers are brought to the surface. It is therefore close to impossible to set and obtain pre-defined patterns with this process, and earlier studies have clearly shown that carving is used for pre-defined patterns. This particular reproduction undertaking aimed to further these studies.

It was possible through observation of the tsuba to determine which metals had been used as well as the layering. A detailed look at the pattern also gave indications as to the manufacturing process. Based on this information, the reproduction proceeded as described below.

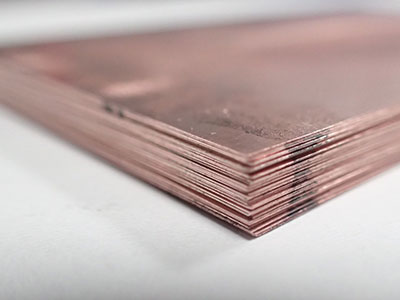

1. Layering and soldering of metal materials (6 layers of shakudo, 6 layers of shibuichi).

2. After forging the layered base metals, they went through a rolling process.

3. Three sheets of the base metal produced as described above were used and forged together.

4. The pattern of blossoms was carved out using a Sakura (cherry-blossom shaped) chisel and an elliptical chisel.

5. Enlargement of carved portion.

6. Completion of cherry blossom and petal design.

7. The carver process continued with wave pattern “Namigata” chisels, with 3 different chisels being used.

8. The surface was filed down with a rasp to bring out the pattern.

9. The Mokume Gane variegations were added.

10. The signature was engraved.

These two tsuba by TAKAHASHI Okitsugu represent not just a “technique to make a pattern” but are works that lifted up the process to representing images. By decorating the entire surface of the tsuba with Mokume Gane waves, it became possible to reproduce the eternal flow of the river stretching out to infinity. They are outstanding works through which he sublimated the technique by producing a design that could only be manifested through Mokume Gane.

There is a detailed explanation regarding the process used in this reproduction study in TAKAHASHI Masaki’s doctoral thesis on “The Decorative Interpretation Possibilities in Mokume Gane Jewelry.”

Please find below an abstract of the relevant parts of the thesis. For further details, please refer to the thesis itself (Japanese only).

********************************************

Reproduction Study 3

Mokume Gane Yoshino River Tsuba Signed TAKAHASHI Okitsugu – The Bigelow Collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Middle part of the Edo period Shakudo and Shibuichi H73.0x W69.0xT5.0mm

Mokume Gane Tatsuta River Tsuba Signed TAKAHASHI Okitsugu, collection of TAKAHASHI Masaki

From times of old, the cherry blossoms on the Yoshino River and the red maple leaves on the Tatsuta River have been favorite topics that have been written about in classics such as the “Manyoshu”, “Kokin Wakashu” and “Shin Kokin Wakashu.”At some stage, these beautiful landscapes transcended reality and leapt into the world of images. What Okitsugu wanted to convey of these landscapes within his tsuba was the “fusion of expression and technique,” taking Mokume Gane into totally new frontiers with these works. Despite the complications entailed in the 8-sided shape, he carefully applied the same material to the totality of the surface, even including the interior of the hitsuana, and by covering the entire tsuba with the design of the flow of the river, he succeeded in making anyone looking at it see the infinity of the river’s flow within the tiny confines of a tsuba.

Observations

The pattern was produced using Mokume Gane that was made of shibuichi and two kinds of shakudo. The streamline shape that represents the flowing water covers the entire surface and, and the works are beautifully balanced with the cheryy blossoms on the Yoshino River tsuba and the red maple leaves on the Tatsuta River tsuba (Plate 15). In addition, the speckling in the pattern gives variations in the river flow design and, as a result, the flow of the river seems to change and has great depth. And then, on the inside of the hitsuana, the variegations that cover the entire surface turn into a different, simpler Mokume Gane than the remainder of the surface. The number of layers was deduced as a result of observations of the surface. If one looks closely, there are several places where one can perceive the cross-section of the layering, such the brim of the hitsuana and the brim of the variegations. And from the structure of the variegations applied to the inside edge of the hitsuana, the cross section of the layering is exposed, and it was possible to see the structure of the layering. The pattern of the Mokume Gane variegation in the front and back of the tsuba and on the inside of the hitsuana is different, but making assumptions based on observation of the front surface pattern, and taking into consideration the fact that it might be unavoidable to use different materials, the conclusion was that the same materials were used in the same number of layers. It was possible to ascertain, from close observation of the way the materials are revealed in the pattern, the order of the manufacturing process. Both the cherry blossoms in the Yoshino River tsuba and the red maple leaves in the Tatsuta River tsuba, are made of just shakudo, and a layering is revealed that seems to surround the shapes of the cherry blossoms and red maple leaves, so that they seem to blend into the surrounding flow of water. From this effect, it was concluded that the cherry blossoms and red maple leaves were carved first with a chisel, followed by the creation of the flowing water. As the same effect can be seen in the speckled pattern, it could be ascertained that the cherry blossom design and the Tatsuta river design were elaborated at the same time.

The greatest characteristic of these two tsuba is the concrete representation of the cherry blossoms and the red maple leaves, which is absolutely unique in the world of Mokume Gane. Basically, Mokume Gane consists of carving the layered materials using chisels or other tools, with a forging process to create a pattern by bringing out the colors of the layers that are underneath. Creating concrete patterns using this process requires great skill in technique, and it is fair to say that making a pattern of complex set designs is close to impossible. However, the author previously proved it by engraving, as reported in the results of the test that was carried out as part of the research report in his book “The Mokume Gane Textbook.” That study was meant to further research on the process of making Mokume Gane, presenting the challenge of reproducing the entire tsuba. Examination showed that that it was a three-layered structure, and in order to gain the full benefits in reproducing the details of the design by engraving, the work was done after the three layers were fused. First, the figurative blossoms were engraved on the fused layers, followed by the circular patterns, and then the patterns that reproduced the flow of the river, in order. This is because if you start by carving the background flowing pattern, it will have an influence on the figurative patterns. The pattern appears as a result of carefully carving out the metal to the level of the indentation. The final step is to wind the same material around the rim and the hitsuana, so that it was possible to experience how, with the entire surface totally covered in Mokume Gane, an image of the flow of a large river could be obtained within the tiny world of a tsuba.

The Results of the Reproduction Study

The Mokume Gane Yoshino River tsuba, made by and signed with TAKAHASHI Okitsugu’s seal, is an outstanding piece within the world of sword fittings made with Mokume Gane techniques, in its combination of technical skill and sensibility. It is the embodiment of a Mokume Gane that went beyond just a technique to make patterns, to a technique to reproduce images. What needs to be emphasized is the elaborateness of creating this design. He was successful in depicting the endless flow of the river on a vast scale with a pattern of waves, imaging and designing an infinite expanse using Mokume Gane that covers the entire surface of the tsuba. In this is depicted the majesty of nature, not by achieving a pattern out of a simple figure, but through the spatial effect of the minute gaps in the metal layers that make Mokume Gane what it is, plus the energy of the material experienced by condensing the density of time. It is no exaggeration to say that, in fact, these scenes can be depicted as such because of Mokume Gane. The condensing of time and energy within the manufacturing process is totally in tune with the themes that are depicted, such as the passing of time and the dignity of nature, and tie in to the inevitability of technique and image. TAKAHASHI Okitsugu’s Yoshino River tsuba (signed TAKAHASHI Okitsugu) is a magnificent example of the realization and surpassing of the technique in a design that could only be realized with Mokume Gane.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 2 Part1

In Boston, in the United States, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is famous for its collection of Far Eastern art.

Boston is known as a trading port and has long engaged in trade with Asia, so the Boston Museum of Fine Arts placed an emphasis on collecting arts from various Asian countries early on.

During the Meiji Era, OKAKURA Tenshin (1862-1913) was invited to serve as curator of Far Eastern Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and he collected a substantial number of Japanese masterpieces. OKAKURA Tenshin had worked on the establishment the Tokyo Fine Arts School (subsequently called the Tokyo University of the Arts), and he founded the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Art Academy), making a major contribution to the world of early modern Japanese art. He also endeavored to make Japanese culture known overseas. As assistant to Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908), he helped him in his purchases of art.

During the Meiji Era, in addition to Fenollosa, other Americans such as William Sturgis Bigelow (1850-1926) were also captivated by Japan, and they studied Japanese art and culture, taking many works of art back home with them, subsequently donating these to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts has an enormous number of important pieces from Japan. For example, in 1986, 514 woodblock printing blocks (the blocks that were carved and then used for making the prints) were re-discovered, including those for Katsushika Hokusai’s illustrated trilogy.

OKAKURA Tenshin Source: “Cha no Hon 100-nen”

The Yoshino River Tsuba of made by TAKAHASHI Okitsugu during the Edo Period, and which represents the culmination of the art of Mokume Gane, is also part of this collection.

We would like to talk here about the connection between this work and Mokumeganeya.

Tatsuta River Tsuba signed TAKAHASHI Okitsugu (Hanaoshi seal)

Middle of the Edo Period Shakudo, Shibuichi

The Two Tsuba

While strolling through antique fairs and shops in search of Mokume Gane works, TAKAHASHI Masaki, founder of Mokumeganeya, came across the “Tatsuta River Tsuba” (photo above) which turned out to be the work of the famous craftsman TAKAHASHI Okitsugu of the Edo Period.

For Takahashi, this was the encounter that prompted him to embark on a lifelong quest for Mokume Gane which had been called the “phantom technique.”

This piece made of Mokume Gane which could show the shape of red maple leaves within its beautiful streamlined pattern.

This image of “red maple leaves floating on the Tatsuta River” exists as a counterpart to the one of “cherry blossoms floating on the Yoshino River.”

They are widely used in Japanese crafts as traditional Japanese designs.

And it seemed only natural that there would be a counterpart tsuba to the one that was obtained by TAKAHASHI.

This counterpart, the “Yoshino River Tsuba” was across the ocean, at the Boston Museum of Fine arts.

Investigative Research On-Site

Having obtained the Tatsuta River tsuba and spent some time studying it, Takahashi and another Mokumeganeya employee finally traveled to Boston in January 2006 to investigate the Yoshino River tsuba at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

During the Edo period, TAKAHASHI Okitsugu made the two tsuba at the same time and he doubtless looked at the two of them together.

So, the next step was for TAKAHASHI to hold in his hands these two tsuba which had been through various owners and ended up for 100 years in Japan and America.

Joe Earle who was Chair of the Department of Art of Asia, Oceania, and Africa, gave us every assistance on-site.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts also has other Mokume Gane and Guribori tsuba in its collection, and we were able to study all of them in the study room that was allocated to us.

Reproduction Study

Based on the study results from that trip, a reproduction study was undertaken on our return of the Yoshino River tsuba, and the results of these more thorough studies are also laid out in details in TAKAHASHI’s doctoral thesis on “The Decorative Possibilities of Mokume Gane jewelry.”

In the second part of this essay, there will be a detailed outline of the reproduction process.

Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 1

The Mokume Gane works that had been metal fittings for swords in the Edo Period started to be collected by foreigners as works of art during the Meiji Period. Even now, there are important collections overseas, displayed in museums such as the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New Work.

The wedding rings that are in your possession are made of this Mokume Gane which has fascinated people all over the world.

Our aim is to continue our studies in this field so that we can strive to make Mokume Gane even more appealing.

Reproduction tsuba of Mokume Gane and other materials,

signed Tsunetada, residing in Kawagoe.

Tsuba of copper, shakudo, and shibuichi Mokume Gane and other materials. Signed Masaki

Reproduction of Mokume Gane Works From the Edo Period

At Mokumeganeya, reproductions are carried out of important Mokume Gane works from the Edo Period held both in Japan and overseas.

By studying that period’s outstanding techniques, we strive to produce new Mokume Gane works.

The current work is a reproduction of a late Edo Period Mokume Gane tsuba which is held at the Baur Foundation Museum of Far Eastern Art in Geneva, Switzerland. This museum started with the works gathered by collector Alfred Baur (1865-1951) and currently holds about 9000 pieces. It is the most important collection of Far Eastern art in Switzerland.

There are 41 pieces that fall into the Mokume Gane and guribori categories, and the museum was very helpful in making these available for us to study on our visit there in March this year.

We were very honored that the piece that was reproduced in May of this year was given the “Effort Prize” at the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords’ Shinsakuto (newly made swords) exhibition.

Facts About Reproduction Studies

The subject of the current reproduction study is a Mokume Gane tsuba that was made by Tsunetada who lived in the later part of the Edo Period in Bushu Kawagoe (the current city of Kawagoe, in Saitama Prefecture).

The characteristic of this work lies in its highly-prized beautiful pattern of overlapping concentric circles, like swirls, known as “Tamamoku.”

The challenge in this reproduction was to recreate faithfully the “Tamamoku” pattern that was a specialty of Tsunetada. Through trial and error, and numerous failed attempts, we were finally able to reproduce realistically the true depth of this pattern.

The process of reproducing a piece starts with making a metal plate of the material. Following investigations, a three-layered metal plate of copper, shakudo and jo-shibuichi was used and was made into a 31-layer stack by firing and compressing.

Tsunetada’s unique “Tamamoku” pattern was recreated by tracing square and oval shapes from the original onto the metal plate, engraving them using a “Tagane” chisel, and then forging it flat using a hammer and roller.

The final product was beaten down from a thickness of 4.65mm to 0.7mm but in doing this, very fine work was required in adjusting the depth, angle and size of the carving, to within 0.1mm to achieve the desired “Tamamoku” pattern.

As a result, it was possible for us to create the complex and unmatched “Tamamoku” pattern that is so utterly self-contained.

The Spirituality of Mokume Gane

As one experiences with all five senses the changes in the metal materials during the manufacturing process, one begins to communicate with these materials, and that is the technique of Mokume Gane that produces these unique patterns.

One can say that it is a technique that incorporates the spirituality of the relationship between the materials and the craftsman.

This applies also to the manufacture of Mokume Gane rings.

The craftsman communes carefully with each and every material so that the patterns you wish for are expressed in the patterns of your ring.