Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 7

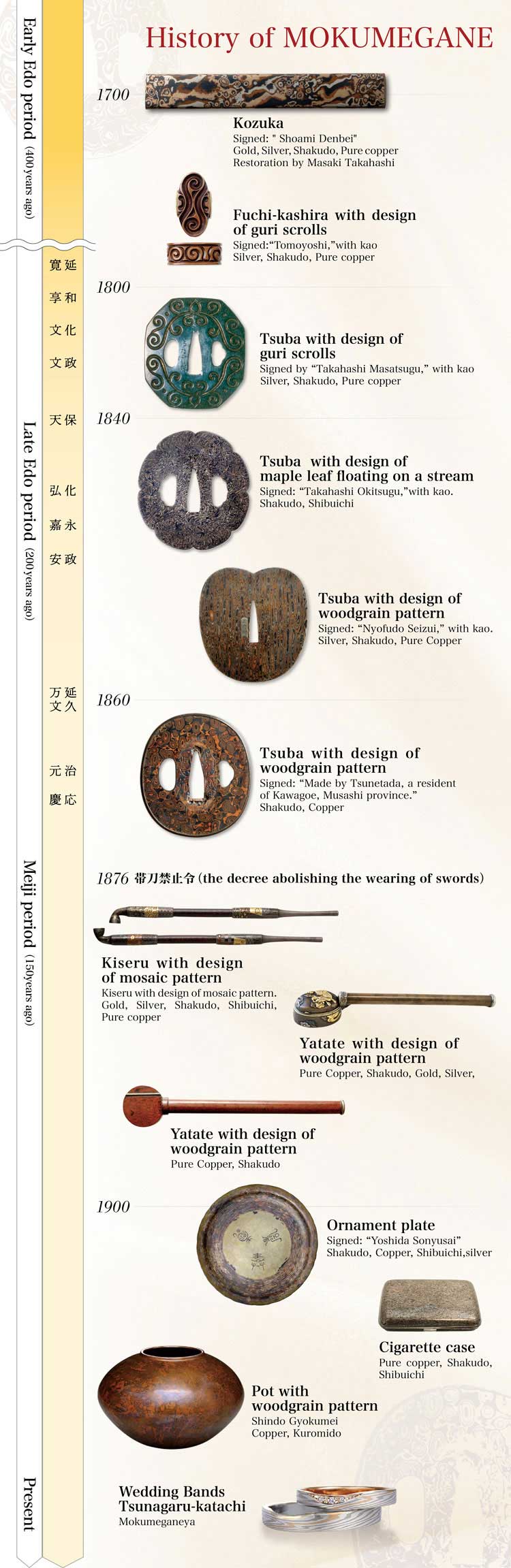

In the previous chapter, we introduced our research and studies concerning Mokume Gane pieces both in Japan and overseas. In this chapter, we would like to tell you about the history of Mokume Gane with an emphasis on Japan’s metal craft as it related to personal accessories.

The Origins of Jewelry in Japan

The origins of jewelry are said to go back to the Paleolithic age, about 12,000 years ago. The evolution was from objects made of stone to those made of bone, shells and wood, as seen in the Jômon period. In those days, it was not so much a question of elegance. Rather, they were used as symbols of authority, or in festivals, or as signs of belonging to a clan, and so evolved very much as tools with a strongly social significance. From the Yayoi period onward, glass, gold, silver and gilt bronze were added to the mix but jewelry continued to circulate, not as ornaments, but having powerful political or religious overtones.

Metal Craft Progressed Apace With Sword Making

In later periods, various crafts were also introduced from the continent, and developed apace with changes in people’s customs and patterns, playing a major role in forging Japanese culture. In particular, it was metal craft that developed independently with the advent of a warrior society in which the sword symbolized the spirit of the warrior. And it was over the 250 years of peace during the Edo period that the art of Japanese metal craft truly flourished. With fewer armed conflicts during the Edo period, the sword went from being a weapon of war to a thing of beauty that was used as an ornament.

The oldest piece of Mokume gane in existence is a kozuka (the handle of a small knife)*1 made by Shoami Denbei, residing in Dewa Akita. It is outstanding by the elegance that comes from the combination of gold, silver, copper and shakudo.

The Development of Personal Accessories During the Edo Period

The techniques for manufacturing personal accessories developed during this period of peace which saw changes in the warrior society as well as the flowering of the merchant culture. The use of these items, starting with kiseru, inro and netsuke, became widespread among warriors and merchants alike. Everyone is now familiar with the typical scenes of merchants with an inro looped around their belt and smoking kiseru that are so common in period dramas. Much effort was put into coordinating the various items, and pieces have come down to us showing the particular humor of the merchant culture that combined the chic and the amusing. Mokume Gane also came to be used in daily accessories such as kiseru and yatate (portable writing boxes) *2. A variety of metal working techniques that had been honed in sword-making, such as the technique of sawing, or openwork, inlay that inserts different colored metals, just as in marquetry, were liberally used.

Changes in Metal Craft Techniques

in the Meiji and Pre-Modern Era

Times, however changed dramatically with the advent of western culture during the Meiji era, and in the 9th year of Meiji (1877) the law forbidding the wearing of swords was passed. The craftsmen who had made a living as swordsmiths turned to making hanging personal accessories or were encouraged to produce pieces for export to make a living. The techniques of Mokume Gane died out for a time following the Haitôrei Edict (prohibiting the wearing of swords) and even came to be known as the “ghost techniques,” but the later enthusiasm and efforts of modern aficionados successfully revived them.

At Mokumeganeya, we have been making a systematic effort to collect, preserve and study the precious techniques of Mokume Gane. We have also overseen the compilation of the Mokume Gane Textbook, and are working to distribute it widely.