Find “Mokume Gane” Chapter 9

Each year, our president, Masaki TAKAHASHI undertakes the reproduction study of an Edo period Mokume Gane piece. His quest, as he does this, is to see how the craftsmen of the time used Mokume Gane techniques to produce their works, and what their frame of mind was as they did so. As he looks at the name of the craftsman of the period inscribed on a sword tsuba, he delves into the relationship between the craftsman and the technique of Mokume Gane as he attempts to reproduce both technique and expression.

In this chapter, we will introduce the process of such a reproduction study so that readers can get something of a feel for the process.

This particular reproduction is of a mid to late Edo period piece signed Shoami Moriaki, residing in Yoshu Matsuyama.

This is the work of the Iyo Shoami school which was located in modern-day Matsuyama, in Ehime Prefecture. Those of you who are familiar with Mokume Gane will doubtless recognize the Shoami name. This is the very same Shoami as in Shoami Denbei who manufactured the kozuka which is considered to be the oldest piece of Mokume Gane. This was a renowned name among metal craftsmen. This school sprang up in the late Muromachi period as metal and tsuba craftsmen, and eventually split into more than 20 branches, including in Kyoto, Iyo, Awa, Aizu, Shonai and Akita. Shoami Katsuyoshi was also famous in the late Bakufu and Meiji periods.

This tsuba by Shoami Moriaki is rather large within the framework of sword tsuba. The shape of the tsuba is descrtibed as “saddle flap” (aorigata), with the width of the lower part rather wider than that of the upper part, giving it a stable shape. Saddle flaps are part of a horse’s equipment and were leather flaps that would be placed on the horses’ body to protect them from mud. Warriors would be familiar with that shape which is why the expression was also used for tsuba shapes. There are also various other tsuba shapes such as fan-shaped (gunbaigata) and quince shaped (bokegata). We will introduce these on another occasion.

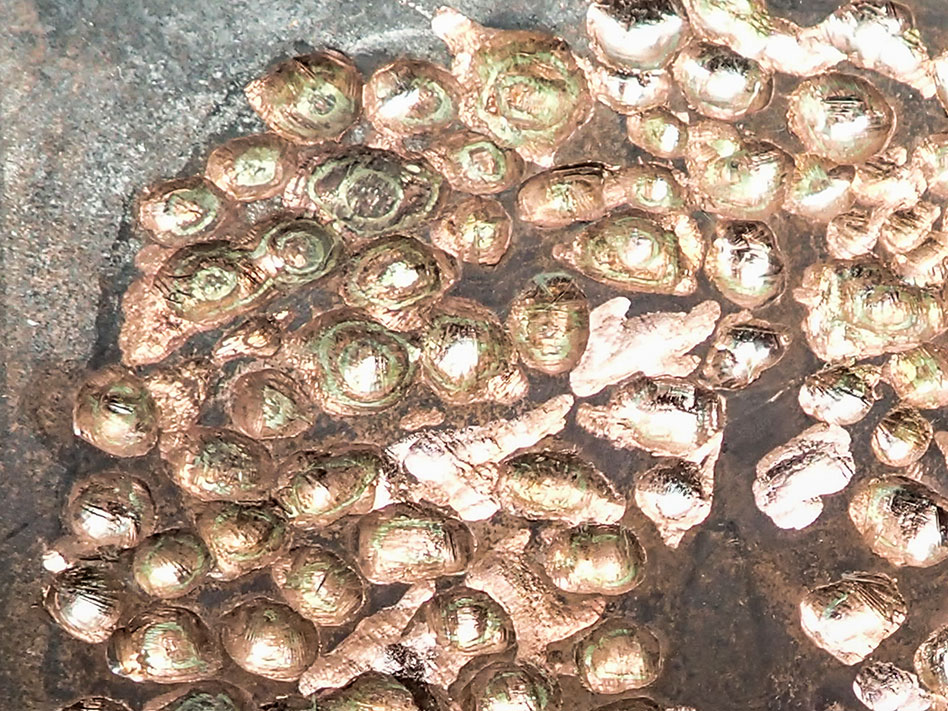

Let’s take a closer look at this tsuba’s Mokume Gane pattern. There is an intricate patterns that covers the entire surface of the tsuba. Could it be the light of the moon at night or perhaps sunshine filtering through foliage reflecting on a gently flowing river, a hard to define, ever-changing pattern. The large and small round burls, known as tamamoku, covering the entire surface, seem to be connecting the drift of the river flow. With copper, shakudo and silver as materials, the landscape is one of interweaving vermillion, black and silver, giving the effect of algae and rocks at the river bottom being visible through the water surface.

That is the concrete landscape and image that the artist wanted to show. In order to do this, he used Mokume Gane techniques, so that Mokume Gane played nothing more than a supporting role to the artist. If one looks back over the history of Mokume Gane tsuba, the Shoami Denbei kozuka that was mentioned earlier, as well as the tsuba made by Morikuni of the Iyo Shoami school, the older the work the more detailed the pattern and the greater use of Mokume Gane as a technique to bring to life the landscapes and views of the world that the artists wanted to show in the tsuba.

Kozuka by Shoami Denbei

Tsuba by Morikuni of the Iyo Shoami school

The years went by and, looking at the tsuba of the late Edo period, they are mostly made of fixed patterns. The boar-eye (inomegata) polished Mokume Gane tsuba such as the one signed Masataka is such an example.

Boar-eye polished Mokume Gata tsuba signed Masataka

The extremely detailed and intricate patterns requires high-level technique, but the pattern of the design is achieved by steady carving in a prescribed fashion. The Mokume Gane technique is entirely being used as the technique to carve the pattern. It was probably standardized with efficiency and productivity in mind. Of course, everyone recognizes it as a piece that embodies Mokume Gane techniques in bringing to life a beautiful pattern. But the technique of Mokume Gane can go beyond that to show something deeper.

This piece by Moriaki is very much in the style of the Iyo Shoami school, looking at first glance like a design that has been made into a pattern, but you can see the traces of how the artist in Moriaki elaborately created the landscape that he wanted to draw.

In carrying out reproduction studies, examination of this type of tsuba leads to imagining the feelings and the aim of the artist, and the manufacturing process is carried out with that same image in mind.

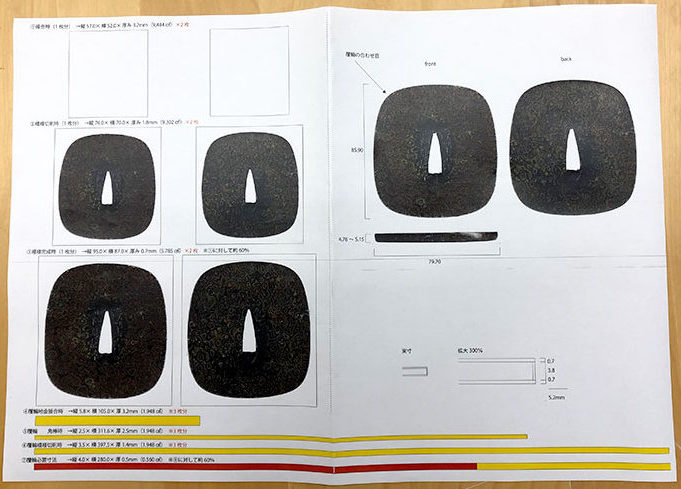

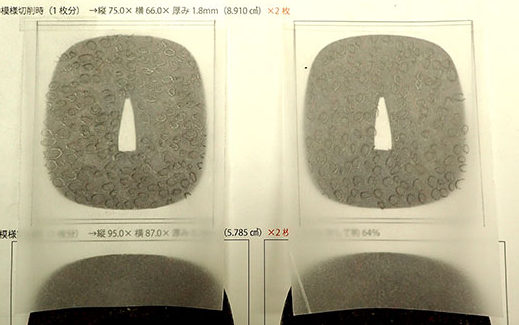

The first step was to determine the metals used from their color, and finding out in which order the various metals were stacked. The pattern that appears to be a flat surface is broken down to its levels by sight, and it is not easy to determine that order correctly in cases where there has been repeated carving and flattening. The next step is to take measurements of the tsuba. Data is obtained on the number of sheets and the thickness of each metal sheet that make up the pattern. This analysis is so that the pattern can be carved initially in a tsuba mold that is smaller than the finished product so that when the final product is flattened and stretched, it is the same size as the original.

The next step is to copy the pattern onto tracing paper from an image that has been reduced from the original tsuba image, and the pattern is then copied on to the metal billet that has been prepared. The billet is made from stacking metal sheets of the thickness that was determined earlier and heat bonding them.

A circular shape is the first thing to be carved. The carving is done carefully while observing the size of the pattern and how the layers appear in the original tsuba. This is because, depending on the depth of the carving and its angle, the color and surface of the pattern will look different on flattening.

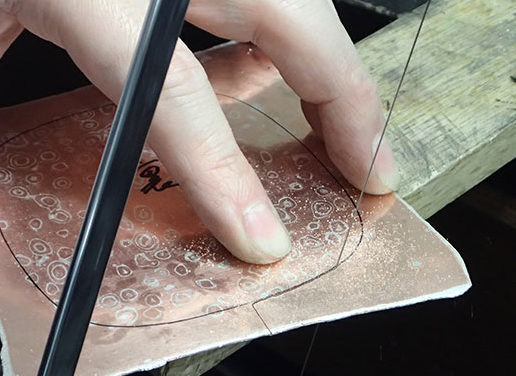

Once the carving is complete, the tsuba is heated and the repetitive job of stretching it to the size of the original is undertaken. The pattern is complete when the surface is quite flat. It is then cut to the shape of the original tsuba.

Once the carving is complete, the tsuba is heated and the repetitive job of stretching it to the size of the original is undertaken. The pattern is complete when the surface is quite flat. It is then cut to the shape of the original tsuba.

The tsuba which was reproduced on this occasion is if the “fukurin” type in which the outer circumference is also made of Mokume Gane. A long and thin billet is carved in the same way, and then stretched flat, and then wound around the edge of the central part of the tsuba.

The front and back of the tsuba are both covered in Mokume Gane and the last thing to be done, depending on the shape of the tsuba, is to inscribe the signature.

The final process for finishing consists of niiro process patination. We will tell you about patination on another occasion but there is a process of soaking in grated daikon radish before boiling in copper sulfate that was a must in the past and is still so today.

There is absolutely no magic in any of this as it is a chemical process that gives a delipidization effect, but it is not quite comprehensible, even in this day and age.

The niiro patination time will vary according to the materials used. The changes in color should be checked from time to time, and care is taken to avoid contact with air.

On completing the reproduction project, what is felt is how the artist used Mokume Gane techniques to bring to life a certain kind of landscape. It is not a collection of patterns that were carved at random but the elaborate manifestation within a tsuba of an image clearly held in the eye of the artist using the attributed of Mokume Gane.